Home » Inflation Indexing (Page 4)

Category Archives: Inflation Indexing

Inflation Index vs Spending

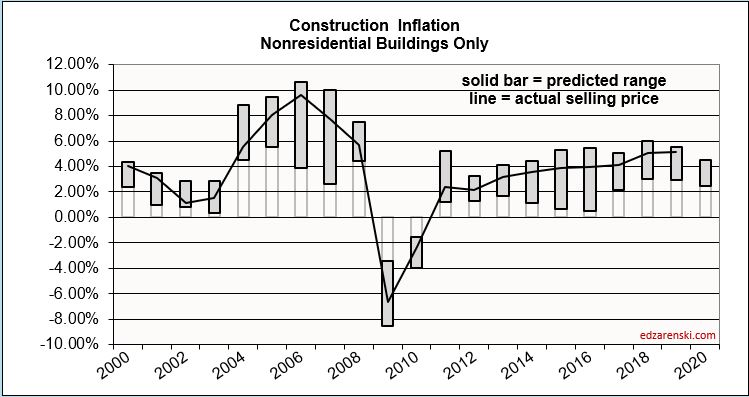

The two plots lined up here represent spending and spending corrected for inflation or real volume growth in the top plot versus construction inflation in the bottom plot. On the Inflation plot, the black line represents final selling price, actual inflation. The red line represents the ENR Building Cost Index which is a fixed market basket of labor and materials, not a complete selling price index. All plots are for nonresidential buildings only.

The index shows how cost inflation climbs in periods when spending is accelerating and the index slows when spending is increasing slowly. Also we can see that the major decline in spending resulted in a major deflation in the index. Note the ENR BCI does not show the major decline in the inflation index. That’s because the ENR BCI is not final selling price. It shows what the cost of labor and materials did during that period, but does not capture how contractors adjusted their margins down so deeply due to loss of volume.

The takeaway from this comparison is this:

- Labor and material indices do not show what real total inflation is doing

- When spending increases rapidly, inflation increases rapidly

- When spending increases slowly, inflation increases slowly

- An understanding of which direction and how much spending is moving is more important to predicting inflation than the change in the cost of labor and materials

Is There a Construction Jobs Shortage?

3-10-17

The imbalance between construction spending and construction jobs is nothing new. It’s been going on for years. It reflects more than just worker shortages. It captures changes in productivity due to activity. It also helps explain why sometimes new jobs growth rates do not follow directly in step with spending growth. A big part is that it reflects hiring practices. That imbalance can be affected by either over or under-staffing and that can be affected by inflation.

2000-2008 The Expansion

For the 1st several years, nonresidential construction spending was flat or down. Then for two years spending was up only slightly, but constant $ volume (spending inflation adjusted) had actually decreased. Nonresidential jobs fell from 2001-2003 but then grew for several years during this period when constant $ volume was decreasing, creating productivity losses.

On the other hand, residential spending grew 80%, but after adjusted for inflation, volume grew only 23%. Most staffing increases during this period were for residential construction and jobs/volume growth was pretty consistent. Residential saw mixed productivity during this period. In 2006 residential volume had already started declining.

It is not uncommon when work is plentiful that productivity declines. In 2004-2005, spending increased by 24%, but inflation was hovering around 8% to 9%/year. Constant $ volume (spending after inflation) increased by only 6%. Jobs grew faster, by 9%. Net productivity decline.

In 2006, nonresidential work was starting to take off, increasing 45% from 2006 though 2008. During this period jobs increased by only 8% and volume added 16%. Excess volume was able to absorb a good portion of the jobs/volume imbalance from 2000-2006.

See the line chart below “Productivity = Annual $ Put-In-Place per worker. These up or down periods for each of these sectors discussed here can easily be seen in rising or falling $PIP volume on that chart, sectors plotted separately. The bar graph “Total Annual Productivity Change”, is the composite total of the three sector graphs.

Net volume in 2006 declined, but jobs increased another 5%. For the three-year period 2004-2006, spending increased by 28%, but after inflation, real volume increased by less than 5%. Jobs increased by 14%. Productivity declined by nearly 10%.

Heading into 2007, residential firms had excess staff, as measured by the negative imbalance of jobs/volume. Compounding productivity issues, when spending started to decrease significantly, it took longer for companies to downsize their workforce. The workforce was not reduced to match the volume of work lost. Residential construction was first to show the strain, already having started to decline in 2006 and continuing to decline through 2009.

2006-2010 The Residential Recession

Residential construction was 1st hit by the recession in early 2006. For the 4 years 2006-2009, residential volume dropped 55%. It remained flat for two more years, down a few more percent. Over six years starting 2006, residential jobs dropped only 40%.

The Annual $ PIP line chart above shows that for 2006-2009 there were only residential losses, or negative balance between jobs/volume. Both nonresidential sectors were improving slightly at the time. The total negative bars in those years is entirely due to residential.

2009-2011 The Nonresidential Recession

Nonresidential Buildings construction didn’t fall into recession until 2009. In the two years 2009-2010, nonresidential buildings lost over 30% in volume but only 22% in jobs.

This chart simply shows the imbalance between the number of jobs and the dollar volume of work put in place for each year compared to the year before. In a simple form that can be referred to as a change in productivity. In all these charts, jobs/year are adjusted for hours worked and dollars are always constant $ inflation adjust to 2016$.

In 2009 my chart shows a huge productivity gain. It is almost entirely due to Non-building infrastructure, which never did fall into deep recession. Combined residential and nonresidential buildings only in 2009 would have shown a net 1% gain.

2011-2012 Early Recovery

Starting 2011, firms had lost significant revenue but had retained more staff than needed. There was so much excess staff (in relation to how much total revenue was available) that almost no reasonable gains in spending could wipe away the losses in productivity. Volume improved by 1%, but hiring resumed and jobs grew by 1%. Due to excess staff still on payrolls, productivity showed a 6% decline.

For the next few years, when we look at jobs growth vs. volume growth, there is reason to believe that slow jobs growth (2011 through 2013) may not be all due to labor shortages. Although we lost more than 2 million jobs, there remained excess jobs when compared to the amount of volume that was available.

At least part of the blame for slower new jobs growth was that excess staff already on hand were being absorb by the new spending gains. For a period there was insufficient volume out in the market to support all the staff that had remained on board. Finally, there was increased revenues which would first reabsorb part of the excess labor before rehiring started.

2012-2016 The Construction Boom

It took three more years to see a significant move towards balancing jobs and real volume. In 2014, jobs increased 6% and constant volume increased 7%. For the first nine months of 2015, jobs increased 3% and volume increased 8%. This was a good productivity balance period.In the three years 2012-2014, volume increased 16% but new jobs grew by only 11%. The increased work volume absorbed a good portion of the excess staffing.

What reasons could cause contractors to think they need more staff?

One reason may be that contractors don’t typically track revenues in constant dollars, they track in current dollars. So any comparison to a previous year is to inflated data. To achieve business plan growth of 6%/year, is it necessary to grow staff by 6%/year? Not if during that period inflation is 4%. Then real volume growth is only 2%/year and new staffing needs are far less than anticipated.

Basing staffing needs on current $ revenue growth can lead to the same kind of over-staffing we saw going into the recession. In the three years 2004-2006, construction spending increased 30%. Jobs increased 16%. However, during that three-year period construction inflation was the highest ever recorded, composite inflation averaging greater than 8%/year. After inflation, real construction volume increased only 4% during that period. Hiring far exceeded the rate of real volume growth. There is the potential that contractor’s hiring could be swayed by highly inflated spending when actually volume is not as strong as thought.

From the Jan 2011 bottom of the construction recession through Dec 2016, both work output (jobs x hours worked) and volume (spending after adjustment for inflation) increased equally by 29%.

(note: BLS revisions to hours worked, issued in the 3-10-17 release changed total growth output from 29% to 30%).

There are always unequal up and down years, but this longer term period shows balanced growth returned after a tumultuous period. We were so far down on the scale after the recession it seems reasonable that we experienced this re-balancing.

Both 2014 and 2015 show productivity gains. That is unusual in that there have not been two consecutive years of productivity gains in 23 years (while my jobs data goes back to 1970, spending data goes back only to 1993).

The trend changed in October of 2015. Now when we look at jobs growth vs. volume growth, there is reason to believe that any jobs growth slow-down may be at least in part due to recent over-hiring.

2014-2016 Record Jobs Growth

In the last three years, we’ve added 840,000 construction jobs. We’ve also increased hours worked to an equivalent to 880,000 jobs, growth of 15%. That’s a faster rate of growth in three years than the 2004-2006 construction boom. To help explain that growth, real volume in 2014-2016 was far greater than the volume in 2004-2006, or any other three-year period for that matter. The last time we’ve seen jobs growth like this was 1995-1999.

2012 through 2016 is the greatest construction boom on record, whether measuring unadjusted current $ spending or constant $ real volume after inflation, flying past the 2000-2005 boom and narrowly beating out 1995-2000. And we started 2017 with backlog at a record level, so the boom continues.

5-Year Construction Booms Compared to 2012-2016

- 2012 – 2016 current $ +$377 bil +48% — constant $ +265 bil +29%

- 2001 – 2005 current $ +$314 bil +39% — constant $ +30 bil <3%

- 1996 – 2000 current $ +$254 bil +46% — constant $ +235 bil +21%

Notice how little growth actually occurred in the five-year period 2001 through 2005. While there was significant spending growth, most of it was inflation, and 90% of it was residential. During that period composite inflation increased more than 35%. Also, nonresidential construction was having a setback, dropping 15% in volume in that five years. The real story out of the 2001-2005 boom period is to compare residential work.

- 2012 – 2016 Rsdn current $ +$211 bil +83% — constant $ +146 bil +46%

- 2001 – 2005 Rsdn current $ +$280 bil +80% — constant $ +132 bil +23%

Residential inflation 2001-2005 was a whopping 47%. But, total residential spending was up 80%. After adjusting for inflation, residential still added 23% to volume during that period. During both periods, residential volume grew more than jobs, so both periods had a net productivity gain.

Also in 2001-2005, nonresidential added 3% more jobs in a five year period in which volume dropped 15%. The very high levels of inflation help explain why staff may have grown to such excess during that period. Contractors were seeing revenues grow by 20%-30% and were slowly adding jobs in a period when real volume was dropping 3% per year.With the exception of residential growth, there was a downturn in other work. New jobs increased by only 11%, but due to rampant inflation, real volume increased by less than 3%. Nonresidential contributed all the negative productivity in 2001-2005.

2014-2015 Construction Spending for the Record Books

- 2014 to 2015 current $ +$206 bil +23% — constant $ +158 bil +16%

No two consecutive years of construction come close to equaling the real volume put-in-place during 2014-2015. The two years 2004-2005 had greater growth in spending, but most of that was inflation, so had little growth in volume. In fact, we would need to consider three consecutive years to come close to 2014-2015 and the three years that comes closest is 1996-1998 and that would still be a few percent short. This volume growth is driving huge jobs growth.

From October 2015 through March 2016, jobs growth was exceptional. During that 6 month period we added 215,000 construction jobs, the fastest jobs growth period in a decade. That period topped off the fastest two years of jobs growth in 10 years. Record increases in jobs growth are not what we might expect if there is a labor shortage.

And yet, the Jobs Opening and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) is the highest it’s been in many years and that is a signal of difficulty in filling open positions. But, one of the known factors during a high level of market activity (lot’s of construction work – we are at record levels) is that workers know there is another and sometimes better job just down the road. During high levels of activity, unless the current employer is paying some kind of premium to keep them, workers may leave for greener pastures. That creates a high level of job churn.

Hiring Changes Lag Volume Changes

It is important to take note that it appears the two most recent six-month surges in jobs lag the period of greatest volume growth. I noted earlier that contractor staffing changes seem to lag movements in volume.

Since Sep 2015, jobs have been increasing more than real construction volume. For much of 2014 and 2015 construction spending real volume growth was exceeding jobs growth. Spending in 2016 slowed from the all-time record levels. That’s not totally unexpected as it would be highly unusual for that record level of growth to continue. But hiring continues.

Since Sept 2015, construction volume growth (spending minus inflation) slowed or stalled and completely contrary to what one would expect in a labor shortage, new jobs growth has been exceeding volume.

- From Sep15 to Mar16 jobs increased+3.3%, volume increased +1.6%

- From Mar16 to Aug16 jobs had no change, volume decreased -3.3%

- From Aug16 to Feb17 jobs increased +2.6%, volume increased +0.10%

This most recent six-month period posted 177,000 jobs, the 3rd best for any consecutive six months since 2005-2006. Although we experienced a slow down in new jobs through the middle of 2016, that was bracketed by two of the three strongest six month growth periods in more than 10 years. For 18 months Sep’15 to Feb’17, jobs are up 7% higher than volume. For 2012-2014 volume grew 6% more than jobs.

For 2017, several economists are predicting total construction spending will increase by just over 6% (including my estimate of 6.5%). However, I’m also predicting that combined construction inflation for all sectors will increase by about 4.5%. That leaves us with a net real volume growth of only 2.0%. Therefore, for 2017, I do not expect jobs to increase by more than 2.0%, or 140,000. That number seems hard to swallow given we are already at 98,000 in the first two months. But remember, jobs have been growing faster than volume for the last 17 months. We could be due for another no-jobs-growth absorption period.

If jobs increase more than 140,000 and both spending and inflation hold to my predictions, then jobs will continue to outpace volume and that will show up on my plot as a productivity loss for 2017. Jobs have been getting ahead of volume for 17 months. Contractors may still be hiring, lagging the movement in real volume growth. It will take the next few months to see if that is the case but I would expect jobs growth to slow or stop for the next few months and I would not attribute that to labor shortages. As we’ve seen before, we should expect jobs/volume to come back to balance. (post note: following Jan-Feb when, after revisions, we added 88k jobs, in the next 5 months we added only 13k jobs. Jobs growth almost stopped for 5 months.)

So, here we are powering our way through the greatest construction expansion ever recorded, with three years of jobs growth at a 11-year high and jobs growing faster than volume for the past 17 months. Does that seem like a jobs shortage to you?

For a continuation of this discussion see A Harder Pill To Swallow! and Construction Jobs Growing Faster Than Volume

Constant Dollars – Impact of Inflation

2-4-17

Current $ vs Constant $

This clearly shows the impact of inflation on comparing Construction Spending data. Reports commonly compare current $1.166 trillion 2016 total spending today back to the (then) current $1.150 trillion at 2006 peak. Of course that seems to establish a new high. But that is so misleading.

Constant $ adjusted for inflation converts all past spending into 2016$ for an equalized comparison. From the low point in 2011 we’ve increased spending by 51% but in constant 2016$ we’ve added only 31% in volume and we are still 16% below the 2005 peak.

As measured in comparable constant dollars, No, we are not back to previous levels of spending. We will probably not return to previous highs before 2020.

The widening gap from right to left, as we look back in time, is the cumulative affect of inflation. It might be only 2% or 4% looking back one year, but back to 2003 it’s 40%.

Impact of Inflation

In all projections, the affect of inflation must be considered. Why is tracking inflation important? Well, as an estimator it’s necessary to assign the appropriate cost to items over time. And it’s needed to properly interpret construction economics. But it’s also important for business management.

Due to construction inflation, a company that was building $700 million in nonresidential buildings in 2005 needs to build $1 billion today just to remain the same size as in 2005. Increasing revenues by 5% annually in a period when inflation is increasing by 5% is not increasing annual volume. While revenue may be increasing, volume would be static. Over a period of years, if this were to occur, since some companies will grow, the amount of volume available to bidders could potentially restrict growth in the number of bidders able to secure new work or in the growth in the size of companies.

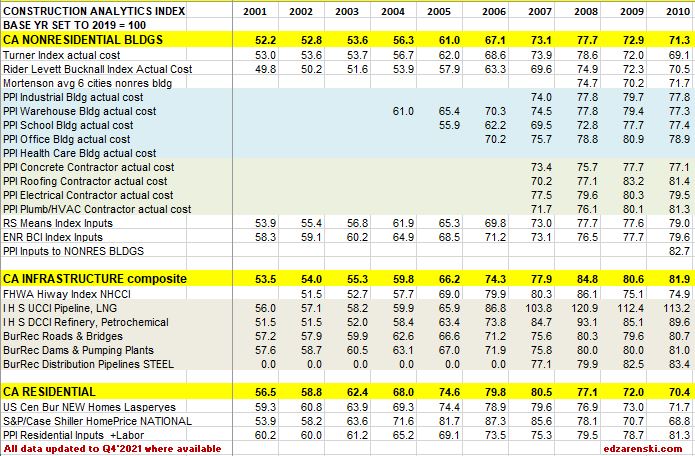

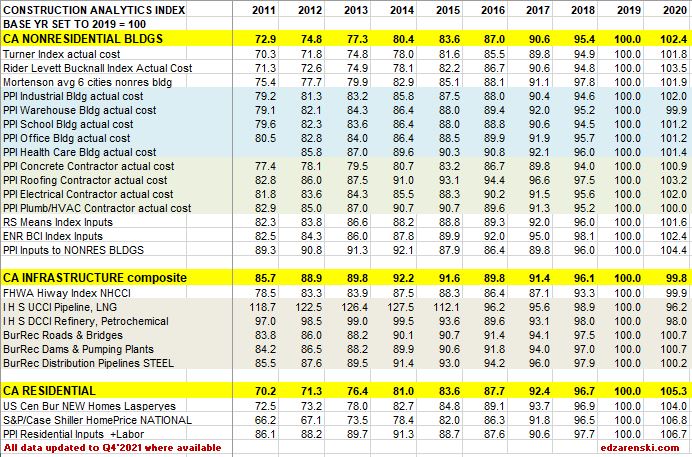

In this table, both the index values and the resultant annual escalation are shown. The index value gives cumulative inflation compared to 2016$.

SEE ALSO these other posts

Are We at New Peak Construction Spending?

Are We at New Peak Construction Spending?

1-4-17

Total construction spending peaked in Q1 2006 at an annual rate of $1,222 billion. For the most recent three months it has averaged $1,172 billion. It is currently at a 10 1/2 year high at just 4% below peak spending. But that ignores inflation.

In constant inflation adjusted dollars spending is still 18% below the Q1 2006 peak.

Current headlines express exuberance that we are now at a 10 1/2 year high in construction spending but fail to address the fact that is comparing dollars that are not adjusted for inflation.

In the 1st quarter of 2006 total spending peaked at a annual rate of $1.2 billion and for the year 2006 spending totaled $1,167 billion. We are within a stone’s throw of reaching that monthly level and 2016 will reach a new all-time high total spending by a slim fraction. But all of that is measured in current dollars, dollars at the value of worth within that year, ignoring inflation.

Adjusting for inflation gives us a much different value. Inflation adjusted dollars are referred to as constant dollars or dollars all compared or measured in value in terms of the year to which we choose to compare. To be fair, we must now compare all backdated years of construction to constant dollars in 2016. What would those previous years be worth if they were valued in 2016 dollars?

By mid-2017 total construction spending will reach a new all-time high, but in constant inflation adjusted dollars will still be 17% below 2006 peak. We will not reach a new inflation adjusted high before 2020.

Residential construction spending is still 32% below the 2006 peak of $690 billion. In constant inflation adjusted dollars it is 39% below 2006 peak.

Nonresidential Buildings construction spending is only 3.5% below 2008 peak of $443 billion. However, in constant inflation adjusted dollars it is 18% below 2008 peak.

Non-building Infrastructure construction spending pre-recession peaked in 2008 at at an annual rate of $290 billion. However, post recession it peaked in Q1 2014 at $314 billion. It is now 8% below the 2014 peak. In constant inflation adjusted dollars it is 12% below the 2014 peak.

For more on inflation SEE Construction Cost Inflation – Midyear Report 2016

Construction Inflation >>> LINKS

- 10-24-16 Originally posted

- 2-11-22 added INFRASTRUCTURE index table Q4 2021

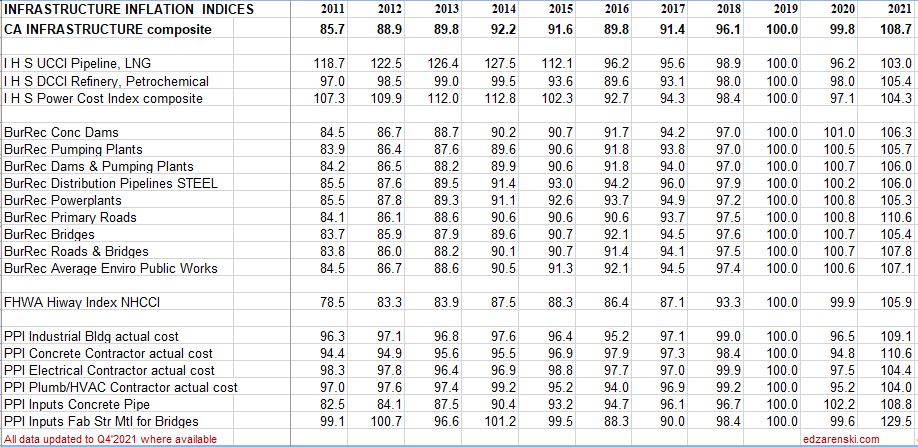

This post is preserved for the multitude of LINKS back to sources of cost indices and for the explanation of the difference between Input indices and Output or Final Cost Indices. For all latest indices plots and table see the latest yearly Inflation post.

2-20-25 SEE Construction Inflation 2025

2-1-23 SEE Construction Inflation 2023

2-11-22 SEE Construction Inflation 2022

11-10-21 See 2021 Construction Inflation

See the article Construction Inflation 2020

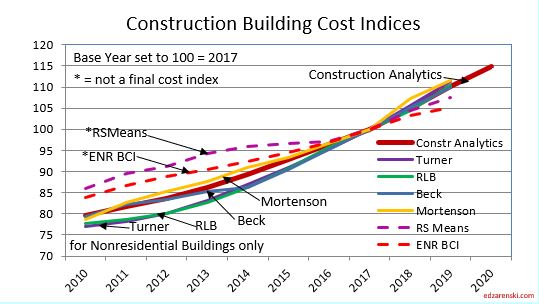

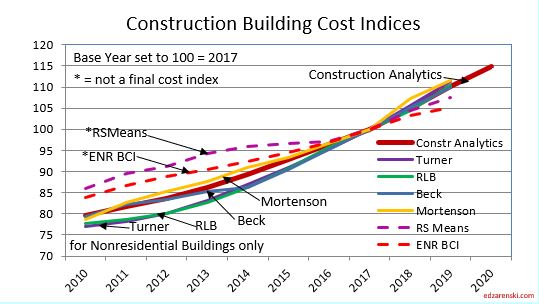

Construction Cost Indices come in many types: Final cost by specific building type; Final cost composite of buildings but still all within one major building sector; Final cost but across several major building sectors (ex., residential and nonresidential buildings); Input prices to subcontractors; Producer prices and Select market basket indices.

Residential, Nonresidential Buildings and Non-building Infrastructure Indices developed by Construction Analytics, (in highlighted BOLD CAPS in the tables below), are sector specific selling price (final cost) composite indices. These three indices represent whole building final cost and are plotted in Building Cost Index – Construction Inflation, see below, and also plotted in the attached Midyear report link. They represent average or weighted average of what is considered the most representative cost indicators in each major building sector. For Non-building Infrastructure, however, in most instances it is better to use a specific index to the type of work.

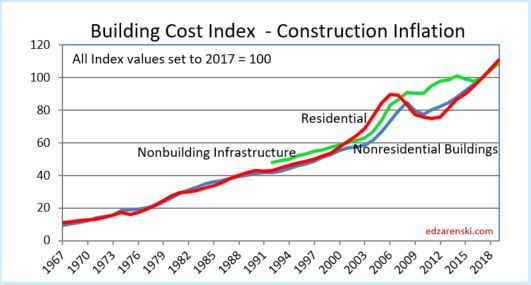

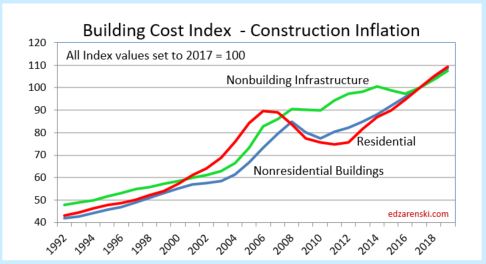

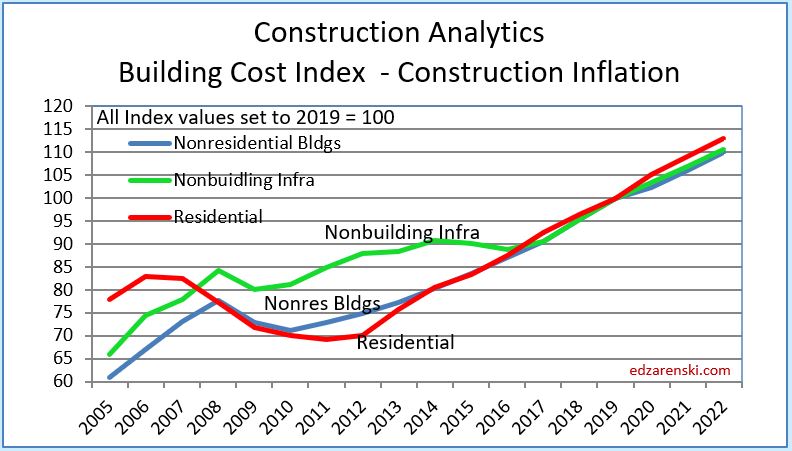

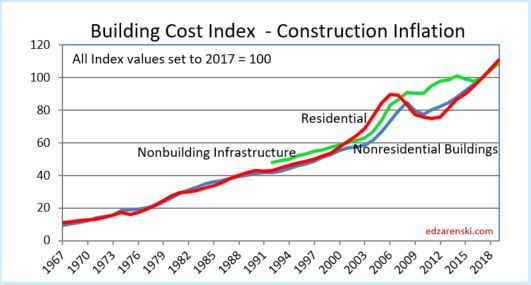

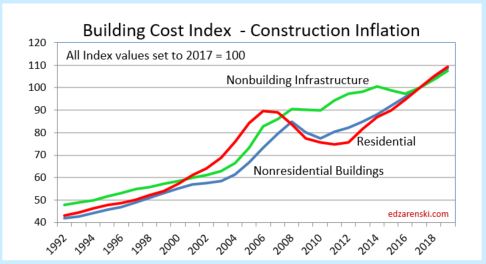

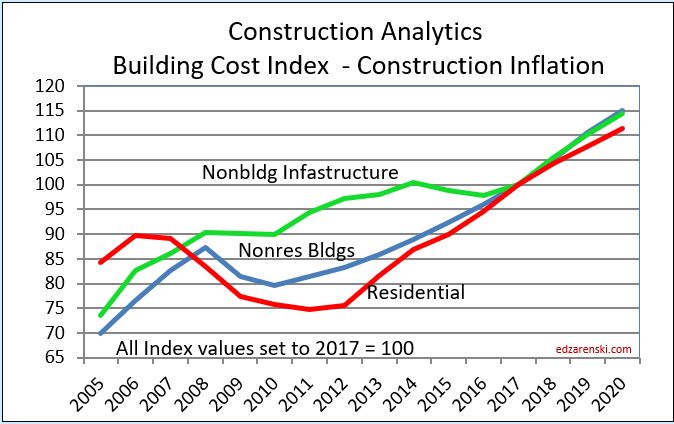

The following plots of Construction Analytics Building Cost Index are all the same data. Different time spans are presented for ease of use.

See the article Construction Inflation 2022

All actual index values have been recorded from the source and then converted to current year 2017 = 100. That puts all the indices on the same baseline and measures everything to a recent point in time, Midyear 2017.

All forward forecast values wherever not available are estimated and added by me.

Not all indices cover all years. For instance the PPI nonresidential buildings indices only go back to years 2004-2007, the years in which they were created. In most cases data is updated to include June 2019.

- June 2017 data had significant changes in both PPI data and I H S data.

- December 2017 data had dramatic changes in FHWA HiWay data.

SEE BELOW FOR TABLES

When construction is very actively growing, total construction costs typically increase more rapidly than the net cost of labor and materials. In active markets overhead and profit margins increase in response to increased demand. When construction activity is declining, construction cost increases slow or may even turn to negative, due to reductions in overhead and profit margins, even though labor and material costs may still be increasing.

Selling Price, by definition whole building actual final cost, tracks the final cost of construction, which includes, in addition to costs of labor and materials and sales/use taxes, general contractor and sub-contractor overhead and profit. Selling price indices should be used to adjust project costs over time.

quoted from that article,

R S Means Index and ENR Building Cost Index (BCI) are examples of input indices. They do not measure the output price of the final cost of buildings. They measure the input prices paid by subcontractors for a fixed market basket of labor and materials used in constructing the building. ENR does not differentiate residential from nonresidential, however the index includes a quantity of steel so leans much more towards nonresidential buildings. RS Means is specifically nonresidential buildings only. These indices do not represent final cost so won’t be as accurate as selling price indices. RSMeans Cost Index Page RS Means subscription service provides historical cost indices for about 200 US and 10 Canadian cities. RSMeans 1960-2018 CANADA Keep in mind, neither of these indices include markup for competitive conditions. FYI, the RS Means Building Construction Cost Manual is an excellent resource to compare cost of construction between any two of hundreds of cities using location indices.

Notice in this plot how index growth is much less for ENR and RSMeans than for all other selling price final cost indices.

8-10-19 note: this 2010-2020 plot has been revised to include 2018-2020 update.

Turner Actual Cost Index nonresidential buildings only, final cost of building

Rider Levett Bucknall Actual Cost Index published in the Quarterly Cost Reports found in RLB Publications for nonresidential buildings only, represents final cost of building, selling price. Report includes cost index for 12 US cities and cost $/SF for various building types in those cities. Boston, Chicago, Denver, Honolulu, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, New York, Phoenix, Portland, San Francisco, Seattle, Washington,DC. Also includes cost index for Calgary and Toronto. RLB also publishes cost information for select cities/countries around the world, accessed through RLB Publications.

Mortenson Cost Index is the estimated cost of a representative nonresidential building priced in seven major cities and average. Chicago, Milwaukee, Seattle, Phoenix, Denver, Portland and Minneapolis/St. Paul.

Beck Biannual Cost Report in 2017 and earlier cost reports developed indices for six major U.S. cities and Mexico, plus average. In the most recent Summer 2021 report, while Beck provides valuable information on cost ranges for 30 different types of projects, the former inflation index is absent. Beck has not published city index values since 2017. Read the report for the trend in building costs. See discussion for Atlanta, Austin, Charlotte, Dallas/Fort Worth, Denver, Tampa and Mexico

Bureau of Labor Statistics Producer Price Index only specific PPI building indices reflect final cost of building. PPI cost of materials is price at producer level. The PPIs that constitute Table 9 measure changes in net selling prices for materials and supplies typically sold to the construction sector. Specific Building PPI Indices are Final Demand or Selling Price indices.

PPI Materials and Supply Inputs to Construction Industries

PPI Nonresidential Building Construction Sector — Contractors

PPI Nonresidential Building Types

PPI Materials Inputs and Final Cost Graphic Plots and Tables in this blog updated 2-10-19

PPI BONS Other Nonresidential Structures includes water and sewer lines and structures; oil and gas pipelines; power and communication lines and structures; highway, street, and bridge construction; and airport runway, dam, dock, tunnel, and flood control construction.

RS MEANS Key material cost updates quarterly

National Highway Construction Cost Index (NHCCI) final cost index, specific to highway and road work only.

The Bureau of Reclamation Construction Cost Trends comprehensive indexes for about 30 different types of infrastructure work including dams, pipelines, transmission lines, tunnels, roads and bridges. 1984 to present.

IHS Power Plant Cost Indices specific infrastructure only, final cost indices

- IHS UCCI tracks construction of onshore, offshore, pipeline and LNG projects

- IHS DCCI tracks construction of refining and petrochemical construction projects

- IHS PCCI tracks construction of coal, gas, wind and nuclear power generation plants

S&P/Case-Shiller National Home Price Index history final cost as-sold index but includes sale of both new and existing homes, so is an indicator of price movement but should not be used solely to adjust cost of new residential construction

US Census Constant Quality (Laspeyres) Price Index SF Houses Under Construction final cost index, this index adjusts to hold the build component quality and size of a new home constant from year to year to give a more accurate comparison of real residential construction cost inflation

TBDconsultants San Francisco Bay Area total bid index (final cost).

Other Indices not included here:

CoreLogic Home Price Index HPI for single-family detached or attached homes monthly 1976-2019. This is a new home and existing home sales price index.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) issued by U.S. Gov. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Monthly data on changes in the prices paid by urban consumers for a representative basket of goods and services, including food, transportation, medical care, apparel, recreation, housing. This index in not related at all to construction and should not be used to adjust construction pricing.

Jones Lang LaSalle Construction Outlook Report National Construction Cost Index is the Engineering News Record Building Cost Index (ENRBCI), a previously discussed inputs index. The report provides some useful commentary.

Sierra West Construction Cost Index is identified as a selling price index with input from 16-20 U.S. cities, however it states, “The Sierra West CCCI plays a major role in planning future construction projects throughout California.” This index may be a composite of several sectors. The link provided points to the description of the index, but not the index itself. No online source of the index could be found, but it is published in Engineering News Record magazine in the quarterly cost report update.

Leland Saylor Cost Index Clear definition of this index could not be found, however detailed input appears to represent buildings and does reference subcontractor pricing. But it could not be determined if this is a selling price index. A review of website info indicates almost all the work is performed in California, so this index may be regional to that area. Updated Index Page

DGS California Construction Cost Index CCCI The California Department of General Services CCCI is developed directly from ENR BCI. The index is the average of the ENR BCI for Los Angeles and San Francisco, so serves neither region accurately. Based on a narrow market basket of goods and limited labor used in construction of nonresidential buildings, and based in part on national average pricing, it is an incomplete inputs index, not a final cost index.

Vermeulens Construction Cost Index can be found here. It is described as a bid price index, which is a selling price index, for Institutional/Commercial/Industrial projects. That would be a nonresidential buildings sector index. No data table is available, but a plot of the VCCI is available on the website. Some interpolation would be required to capture precise annual values from the plot. The site provides good information.

CALTRANS Highway Cost Index Trade bids for various components of work and materials, published by California Dept of Transportation including earthwork, paving and structural concrete. Includes Highway Index back to 1972, quarterly from 2012.

Colorado DOT Construction Cost Index 2002-2019 Trade bids for various components of work published by Colorado Dept of Transportation including earthwork, paving and structural concrete.

Washington State DOT Construction Cost Index CCI for individual components or materials of highway/bridge projects 1990-2016

Minnesota DOT Highway Construction Cost Index for individual components of highway/bridge projects 1987-2016

Iowa DOT Highway Cost Index for individual components of highway/bridge projects 1986-2019

New Hampshire DOT Highway Cost Index 2009-2019 materials price graphs and comparison to Federal Highway Index.

New York Building Congress New York City Construction Costs compared to other US and International cities

U S Army Civil Works Construction Cost Index CWCCIS individual indices for 20 public works type projects from 1980 to 2050. Also includes State indices from 2004-2019

Eurostat Statistics – Construction Cost Indices 2005-2017 for European Countries

Comparative International Cities Costs – This is a comparative cost index comparing the cost to build in 40 world-wide cities If this International Cities Costs is a parity index, which involves correcting for difference in currency, then you must know the parity city in each country, which in the US I think is Chicago.

OECD International Purchasing Power Parity Index

Turner And Townsend International Construction Markets 2016-2017

Turner And Townsend International Construction Markets 2018

Rider Levitt Bucknall Caribbean Report 2018

US Historical Construction Cost Indices 1800s to 1957

Click Here for Link to Construction Cost Inflation – Commentary

2-12-18 – Index update includes revisions to historic Infrastructure data

1-26-21 The tables below, from 2011 to 2020 and from 2015 thru 2023, updates 2020 data and provides 2021-2023 forecast.

NOTE, these tables are based on 2019=100. Nonresidential inflation, after hitting 5% in both 2018 and 2019, and after holding above 4% for the six years 2014-2019, is forecast to increase only 2.5% in 2020, but then 3.8% in 2021 and hold near that level the next few years. Forecast residential inflation for the next three years is level at 3.8%. It was only 3.6% for 2019 but averaged 5.5%/yr since 2013 and returned to 5.1% in 2020.

11-10-21 Follow the link at the bottom to 2021 Inflation

The Tables below 2001 to 2010 and 2011-2020 are updated to Q4 2021 with any revisions to past years posted on source websites.

The Table below 2015 to 2023 is updated to Q4 2021

How to use an index: Indexes are used to adjust costs over time for the affects of inflation. To move cost from some point in time to some other point in time, divide Index for year you want to move to by Index for year you want to move cost from. Example : What is cost inflation for a building with a midpoint in 2022, for a similar nonresidential building whose midpoint of construction was 2016? Divide Index for 2022 by index for 2016 = 110.4/87.0 = 1.27. Cost of building with midpoint in 2016 x 1.27 = cost of same building with midpoint in 2022. Costs should be moved from/to midpoint of construction. Indices posted here are at middle of year and can be interpolated between to get any other point in time.

All forward forecast values, whenever not available, are estimated by Construction Analytics.

2-13-23 Construction Inflation 2023

Steel Statistics and Steel Cost Increase Affect on Construction?

9-18-16 update Mar 2018

Recent articles suggest that steel cost is expected to increase and this will almost certainly affect the cost of construction. But just how much of an affect would a cost increase have on total building cost? The cost increase that is being talked about is the mill price cost of steel, or something like pipe and tube producer price (PPI), since pipe and tube is a world trade item, but not a Fab Steel PPI. None of these include total cost of steel installed. The PPI is the price after fabrication. Total cost is the contractor’s bid or selling price installed which includes all markups (or markdowns).

PPI Steel Materials Inputs plot updated 2-10-19 to include 2018 data

The questions we need to answer are:

- How much of a cost increase will we see in the raw product, manufactured raw steel?

- How much steel is used in a building?

- What affect will a raw material cost increase have on the cost of steel installed?

- How much does that change the cost of the building?

It might help to start with a basic understanding of steel manufacturing and use.

Basic Oxygen Steel (BOS) steel making uses between 25 and 35% recycled steel to make new steel. BOS steel usually has less residual elements in it, such as copper, nickel and molybdenum and is therefore more malleable than EAF steel so it is often used to make automotive bodies, food cans, industrial drums or any product with a large degree of cold working. Cold rolled steel is in this category which would include gypsum wall system steel studs and HSS Hollow Structural Sections.

Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) steel making contains more residual elements that cannot be removed through the application of oxygen and lime. It is used to make structural beams, plates, reinforcing bar and other products that require little cold working. EAF steel uses almost 100% recycled steel. Most steel that goes into a building or civil structure is in this category. 2/3rds of all steel manufactured in the US is EAF steel.

Typically quoted benchmark steel pricing that I’ve seen is based on either cold-rolled-coil sheet steel or hot-rolled-coil sheet steel. This is a common product used for the automotive industry or appliance, but not so much for the construction industry (steel studs vs structural steel). EAF Structural steel is nearly 100% dependent on recycled steel so is not as much affected by price changes of iron ore, as is BOS steel.

The United States is the world’s largest steel importer. Of the 30MMT imported, 50%+ of that comes from our top few import suppliers, Canada, Brazil, South Korea and Mexico. Russia supplies 7%-9%. No other country supplies more than 5% of our imports. China supplies less than 2% of our steel imports, The U.S. is responsible for almost 10% of global steel imports, more than double the second largest importer. The U.S. annually imports about $20-$25 billion of steel, $2 billion from Mexico.

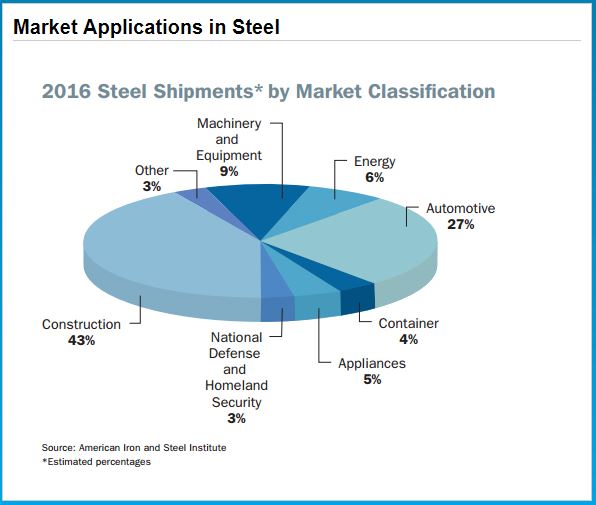

The United States consumes approximately 110 million tons of steel each year. More than 40 million tons is used in the construction industry. The next largest industries, automotive and equipment and machinery, together do not use as much steel as construction. The U.S. imports about 30% of the steel it uses.

The graphic chart above is by American Iron and Steel Institute.

Structural steel is the most widely used structural framing material for buildings used in the U.S. with nearly 50% market share in nonresidential and multistory residential buildings. Prior to the recession steel had a 60% market share.

Sources are also linked below.

What affect might a steel cost increase have on a building project? It will affect the cost of structural shapes, steel joists, reinforcing steel, metal deck, stairs and rails, metal panels, metal ceilings, wall studs, door frames, canopies, steel duct, steel pipe and conduit. Structural steel and reinforcing steel are hot-rolled long products, EAF steel. All the others are cold-rolled flat sheet BOS steel.

Here are some averages of the percentage of steel material costs as related to total project construction cost. For a building that is predominantly masonry, these percentages would be reduced considerably. For a heavy industrial building the percentages might be higher.

Assuming a typical structural steel building with some metal panel exterior, steel pan stairs, metal deck floors, steel doors and frames and steel studs in walls, then all steel material installed represents about 14% to 16% of total building cost.

Structural Steel only, installed, is about 9% to 10% of total building cost, but applies to only 60% market share of steel buildings. The other 6% of total building cost applies to all buildings.

Other steel is very likely higher to take into account any increased cost in major mechanical equipment such as chillers, pumps, fan powered boxes, cooling towers, tanks, generators, plumbing fixture supports, electrical panel boxes and cable trays.

If the structural steel subcontractor increases bid price by 10%, that raises the cost of the building by 1%, but if it is the mill price of steel that increases by 10% the increase to final building price is far less. It is the mill price of steel, rather than fabricated steel, that you would track in the producer price index (PPI).

The final cost of steel installed in a building is about four times the cost of the raw mill steel material used in making and installing the final product. Why so different? Well, for instance, structural steel cost includes: raw mill steel cost, delivery to shop, drafting, shop fabrication, shop paint, delivery to job site and shop markup. At the job site it includes: unload and sort, field installation crew, welding machine, crane and operator, contractor’s overhead and profit and sales tax.

Assuming a building as described above, a 10% increase in the cost of mill steel, which (material only) affects one fourth the cost of 16% of the total building cost, then a 10% increase in the cost of ALL mill steel may result in a composite price increase on a whole building of about 10% x ¼ x 16% = 0.4%. A 10% increase in the cost of mill steel just for structure may result in a composite price increase on a whole building of about 10% x ¼ x 10% = 0.25%.

So, if the mill cost of steel were to increase 10% from $700/ton to $770/ton prior to shop fabrication, for a $100 million building, that could add roughly 0.25% ($250,000) to the cost of the structural steel contract or roughly 0.4% ($400,000) to the total cost of all steel.

A 25% increase in mill steel could add 0.65% to final cost of building just for structure. It adds 1.0% for all steel in a building.

For a project such as a steel bridge, where not just 16% of cost is steel material, but potentially 40% to 60% of cost is steel, a 25% increase in mill steel might add as much as 3% to 4% to final cost.

links to relevant data

Steel Imports Report Global Steel Trade Monitor

Steel Capacity Utilization and Use American Iron and Steel Institute

Structural Steel Industry Overview AISC

World Steel Production – Consumption – Imports – Exports

Crain’s NY – Impact of steel tariffs already being felt in NYC

Construction Cost Inflation – Commentary 2019

1-28-20 See the new post Construction Inflation 2020

8-10-19 updated plots and commentary

General construction cost indices and Input price indices that don’t track whole building final cost do not capture the full cost of escalation in construction projects. To properly adjust the cost of construction over time you must use actual final cost or selling price indices.

Click Here for Link to a 20year Table of 25 Indices

Inflation in construction acts differently than consumer inflation. When there is more work available, inflation increases. When work is scarce, inflation declines. A very large part of the inflation is margins, wholesale, retail and contractor. When nonresidential construction was booming from 2004 through 2008, nonresidential final price inflation averaged almost 8%/year. This was at a time when input costs were averaging between 5% and 6%/year. When residential construction boomed from 2003 to 2005, inflation in that sector was 10%/year. But from 2009 through 2012 we experienced deflation, the worst year being 2009. Residential construction experienced a total of 17% deflation from 2007 through 2011. From 2008 to 2010, nonresidential buildings experienced 10% deflation in two years.

The following plots are all the same data. Different time spans are presented for ease of use.

8-10-19 note: this 2005-2020 plot has been revised to include 2018-2020 update.

Nonresidential Buildings – Since 1993, the 25-year long-term annual construction inflation has averaged 3.5%, even when including the recessionary period 2007-2011. Long-term average inflation, without recessionary declines, is 4% for 20 non-recessionary years since 1993. During rapid growth period of 5 years from 2004-2008, inflation averaged 8% per year. Since 2011, nonresidential buildings inflation has averaged 3.8%, averaging 4.25%/yr. for the last 4 years with a high of 5.1% in 2018.

Residential, from 2007- 2011 experienced 5 consecutive years of deflation, down 20%. In the 4-year boom just prior to that, 2003-2006, inflation averaged 9% per year. Residential inflation snapped back to 8.0% in 2013. It slowed to 4.4% in 2018 but has averaged over 5% for the last three years.

Construction Spending growth posted two separate 4-year periods of 40%+ growth, up 41% in 2012-2015 and up 40% in 2013-2016, exceeding the growth during the closest similar four-year periods 2003-2006 (+37%) and 1996-1999 (+36%), which were the two fastest growth periods on record with the highest rates of inflation and productivity loss. Growth peaked at +11%/year in 2014 and 2015, exceeded only slightly by 2004-2005.

Spending growth slowed to 7.0% in 2016 and only 4.5% in 2017. In 2018, spending dropped to a gain of only 3.3%. It’s expected, after revisions that 2019 spending will finish at a gain of less than 2%.

Producer Price Index (PPI) Material Inputs (excluding labor) costs to new construction increased +4% in 2018 after a downward trend from +5% in 2011 led to decreased cost of -3% in 2015, the only negative cost for inputs in the past 20 years. Input costs to nonresidential structures in 2017+2018 average +4.2%, the highest in seven years. Infrastructure cost are up near 5% and single-family residential inputs are up 4%. But material inputs accounts for only a portion of the final cost of constructed buildings.

Labor input is currently experiencing cost increases. When there is a shortage of labor, contractors may pay a premium to keep their workers. All of that premium may not be picked up in wage reports. Also, some of the labor inflation is due to lost productivity due to less skilled workforce. Unemployment in construction is the lowest on record. There is some sign of jobs growth slowing down in Q2 and Q3 2019, and potentially getting slower.

Nationally tracked indices for residential, nonresidential buildings and non-building infrastructure vary to a large degree. When the need arises, it becomes necessary that contractors reference appropriate sector indices to adjust for whole building costs.

Click Here for Link to a Table of 25 Index Values

ENRBCI and RSMeans input indices are prefect examples of commonly used indices that DO NOT represent whole building costs, yet are widely used to adjust project costs. An estimator can get into trouble adjusting project costs if not using appropriate indices. The two input indices for nonresidential buildings did not decline during the 2008-2010 recession. All other final cost indices dropped 6% to 10%.

From 2010 to 2019, total final price inflation is 110/80 = 1.38 = +38%. Input cost indices total only 106/85 = 1.25 = +25%, missing a big portion of the cost growth over time.

CPI, the Consumer Price Index, tracks changes in the prices paid by urban consumers for a representative basket of goods and services, including food, transportation, medical care, apparel, recreation, housing. This index in not related at all to construction and should never be used to adjust construction pricing. Historically, Construction Inflation is about double the CPI. However for the last 5 years it averages 3x the CPI.

Taking into account the current (Jan 2018 12 mo) CPI of 2% and the most recent 5 years ratio, along with accelerated cost increases in labor and material inputs and the high level of activity in markets, I would consider the following forecasts for 2018 inflation as minimums with potential to see higher rates than forecast.

Residential construction, from 2007- 2011, experienced five consecutive years of deflation, down 20%. In the 4-year boom just prior to that, 2003-2006, inflation averaged +9% per year. Residential construction inflation saw a slowdown to only +3.5% in 2015. However, the average inflation for five years from 2013 to 2017 is 6%. It peaked at 8% in 2013. It climbed back over 5% for 2016 and reached 5.8% in 2017. For 2018, residential final cost inflation indexes are up only 4.5%. Residential construction inflation for 2019 is now about 4% to 4.5%.

A word about Hi-Rise Residential. About 95% of the cost of a hi-rise residential building would remain the same whether the building was for residential or nonresidential use. This type of construction is totally dis-similar to low-rise residential, which in large part is stick-built single family homes. Therefore, a more appropriate index to use for hi-rise residential construction is the nonresidential buildings cost index.

Nonresidential Buildings inflation, during the rapid growth period of five years from 2004-2008, averaged 8% per year. Inflation averaged near 4% per year for the 4 years 2014-2017.

Several Nonresidential Buildings Final Cost Indices averaged over 5% per year for the last 2 years and over 4% per year for the last 5 years. Nonresidential buildings inflation totaled 22% in the last five years. Input indices that do not track whole building cost would indicate inflation for those four years at only 12%, much less than real final cost growth. For a $100 million project escalated over those four years, that’s a difference of $8 million, potentially underestimating cost.

Nonresidential buildings spending slowed from 2017 to 2019 but is now entering a phase in which it may reach the fastest rate of growth in three years, which historically leads to accelerated inflation. Construction inflation for nonresidential buildings for 2018 and 2019 was 5%/yr. For 2020 expect 4.25%, rather than the long term average of 3.5% to 4.0%.

Non-building infrastructure indices are so unique to the type of work that individual specific infrastructure indices must be used to adjust cost of work. The FHWA highway index increased 17% from 2010 to 2014, stayed flat from 2015-2017, then increased 6%+ in 2018. The Highway index for 2019 is up about 6%. The IHS Pipeline and LNG indices increased in 2018 but are still down 20% since 2014. Coal, gas, and wind power generation indices have gone up only 6% in seven years. Refineries and petrochemical facilities have dropped 5% in 4 years but 2018 regained the level of 2013. Input costs to infrastructure are down slightly from the post recession highs, but most have increased in the last year. Input cost to Highways are up 5.0% and to the Power sector are up 3.6% in 2018. Work in Transportation and Pipeline projects has increased dramatically in 2017 and 2018.

Infrastructure power indices registered 2.5% to 3.5% gains in 2017 and again in 2018. Highway indices increased 6.6% in 2018. Anticipate 4% inflation for Power sector and at least 5%-6% inflation for Highway in 2019 with the potential to go higher in rapidly expanding markets, such as pipeline or highway.

This plot for nonresidential buildings only shows bars representing the predicted range of inflation from various sources with the line showing the composite final cost inflation. Note that although 2015 and 2016 have a low end of predicted inflation of less than 1%, the actual inflation is following a pattern of growth above 4%. The low end of the predicted range is almost always established by input costs, while the upper end of the range and the actual cost are established by selling price indices.

8-10-19 note: this 2005-2020 plot has been revised to include 2018-2020 update.

A word about terminology: Inflation vs Escalation. These two words, Inflation and Escalation, both refer to the change in cost over time. However escalation is the term most often used in a construction cost estimate to represent anticipated future change, while more often the record of past cost changes is referred to as inflation. Keep it simple in discussions. No need to argue over the terminology, although this graphic might represent how most owners and estimators reference these two terms.

In every estimate it is always important to carry the proper value for cost inflation. Whether adjusting the cost of a recently built project to predict what it might cost to build a similar project in the near future or adding an escalation factor to the summary of an estimate for a project with a midpoint 2 years out, or answering a client question, “What will it cost if I delay my project start by one year?”, whether you carry the proper value for escalation can make or break your estimate.

- Long term construction cost inflation is normally about double consumer price inflation (CPI).

- Since 1993 but taking out 2 worst years of recession (-8% to -10% total for 2009-2010), the 20-year average inflation is 4.2%.

- Average long term (30 years) construction cost inflation is 3.5% even with any/all recession years included.

- In times of rapid construction spending growth, construction inflation averages about 8%.

- Nonresidential buildings inflation has average 3.7% since the recession bottom in 2011. It averaged 4.6% for the 4 years 2016-2019.

- Residential buildings inflation reached a post recession high of 8.0% in 2013 but dropped to 3.5% in 2015. It averaged 4.6% for the 4 years 2016-2019, but is at the low point of 3.3% in 2019.

- Although inflation is affected by labor and material costs, a large part of the change in inflation is due to change in contractors/suppliers margins.

- When construction volume increases rapidly, margins increase rapidly.

- Construction inflation can be very different from one major sector to the other and can vary from one market to another. It can even vary considerably from one material to another.

Click Here for Link to a Table of 25 Index Values

Construction Inflation Cost Index

Note: The post you’ve reached here was originally written in Jan 2016. For the latest information follow this link to the newest data on Inflation. 8-15-19

ESCALATION / INFLATION INDICES

Thank You. edz

Jan. 31, 2016

Construction inflation for buildings in 2016-2017 is quite likely to advance stronger and more rapidly than some estimators and owners have planned.

Long term construction cost inflation is normally about double consumer price inflation. Construction inflation in rapid growth years is much higher than average long-term inflation. Since 1993, long-term annual construction inflation for buildings has been 3.5%/yr., even when including the recessionary period 2007-2011. During rapid growth periods, inflation averages more than 8%/yr.

For the period 2013-2014-2015, nonresidential buildings cost indices averaged just over 4%/yr. and residential buildings cost indices average just over 6%/yr. I recommend those rates as a minimum for 2016-2017. Some locations may reach 6% to 8% inflation for nonresidential buildings but new work in other areas will remain soft holding down the overall average inflation. Budgeting should use a rate that considers how active work is in your area.

Infrastructure projects cost indices on average have declined 4% in the last three years. However, infrastructure indices are so unique that individual specific indices should be used to adjust cost of work. The FWHA highway index dropped 4% in 2013-2014 but increased 4% in 2015. The IHS power plant cost index gained 12% from 2011-2014 but then plummeted in 2015 to an eight year low. The PPI industrial structures index and the PPI other nonresidential structures index both have been relatively flat or declining for the last three years.

These infrastructure sector indices provide a good example for why a composite all-construction cost index should not be used to adjust costs of buildings. Both residential and infrastructure project indices often do not follow the same pattern as cost of nonresidential buildings.

Anticipate construction inflation of buildings during the next two years closer to the high end rapid growth rate rather than the long term average.

Construction Inflation

LINK to most recent articles on inflation 2019

11-17-2015

( Also See 1-31-2016 comments and chart on inflation )

Over the last 24 months work volume has increased and short-term construction inflation has increased to more than double consumer inflation. It appears construction inflation is already advancing faster than and well ahead of consumer inflation, which supports that consumer inflation is not an indication of movements or magnitude of construction inflation.

It is always important to carry the proper value for cost inflation. Whether adjusting the cost of a recently built project to predict what it might cost to build a similar project in the near future or answering a client question “What will it cost if I delay my project start by one year?”, whether you carry the proper value for inflation (which can differ every year) can make or break your estimate.

- Long term construction cost inflation is normally about double consumer price inflation (CPI).

- Since 1993 but taking out 2 years of recession (-8%), the 20-year average inflation is 4.2%.

- Average long term (30 years) construction cost inflation is 3.5% even with any/all recession years included.

- In times of rapid construction spending growth, construction inflation averages about 8%.

- Although inflation is affected by labor and material costs, a large part of the change in inflation is due to change in contractors/suppliers margins.

- When construction volume increases rapidly, margins increase rapidly.

- Construction inflation can be very different from one major sector to the other and can vary from one market to another. It can even vary considerably from one material to another.

In the 5 years of rapid growth in spending for nonresidential buildings from 2004 through 2008, nonresidential buildings cost inflation totaled 39%, or averaged ~8% per year.

In the 6 years of spending during the residential construction boom from 2000 through 2005, residential building cost inflation totaled 47%, or averaged ~8% per year.

Neither the producer price index (PPI) for construction inputs nor the CPI are good indicators of total construction cost inflation.

Some construction cost indices include only the cost changes for a market basket of labor and materials and do not include any change for margins. Those indices are not a complete analysis of construction cost inflation.

Construction cost inflation must include all changes related to labor wages, productivity, materials cost, materials availability, equipment and finally contractors margins. Margins are affected by the volume growth of new work and demand for new buildings. So be sure to verify what is included in any cost index you reference for real construction cost inflation.

For the last three years residential construction inflation has averaged 5.7% and nonresidential buildings inflation has averaged 4.2%. Nonresidential buildings cost inflation has increased for five consecutive years. Both are likely to increase next year since anticipated volume in both sectors will grow next year.

In my construction spending data set, which goes back to 1993, there were six years with greater than 9% spending growth. By far the largest spending growth years were 2004 and 2005, 11.2% and 11.5%. We are about to repeat that historic level of spending growth. I am predicting 2015 will finish with growth of 11.6% and 2016 will experience 11% growth.

(8-12-16) 2015 finished at 10.6% because 2014 was revised up. Construction spending for 2016 will probably finish closer to 8%.

I expect historic levels of growth in spending will be accompanied by inflation relative to historic high growth periods. Don’t expect long term average inflation in high growth periods. Don’t be caught short in your construction cost budgets!

Graphic updated 1-8-16

The chart shows the low and high range of various independent nonresidential buildings construction actual cost indices. In 2015, the range of estimates was from 2% to 5%. The actual inflation came in at 4%. The plotted line is my result of where inflation actually ended up. A chart for residential construction would show much different values.

( Also See 1-31-2016 comments and chart on inflation )