Home » Posts tagged 'Featured'

Tag Archives: Featured

Pandemic Impact on Construction – Recession in 2020?

This analysis attempts to develop the resulting impact of a construction recession scenario caused by the current Covid-19 pandemic. The scenario presented does not assume a catastrophic failure of the U.S. economy, but does assume a large drop in construction activity in 2020 and 2021.

This analysis generates spending cash flows from current and assumed reduced new construction starts to then determine how spending may affect future construction activity.

Impact of Pandemic on Construction

Analysis of a Recession Scenario 2020-2022

by Ed Zarenski 3-20-20

The change around us is happening so fast, in my opinion, no one is ready for what comes next.

The world is struggling to get the upper hand in a pandemic, travel is coming to a near halt, stock markets are down 30% in a month, universities have sent students home, schools and businesses are closed until further notice, events all around the country are being canceled and people are being instructed to stay home and limit social contact.

We won’t get the first hard data of Coronavirus impacts on the construction industry spending and jobs until reports released in first week in May which will cover jobs mid-March thru mid-Apr and spending for March. The first hint at what we might expect regarding slowdown could be the Dodge construction starts for March which comes out around Apr 20. But spending and jobs from work in backlog coming out in the May reports could be better 1st indicator.

Firms that manufacture goods used in construction may be closed temporarily, so they are producing less. Shipping of products on world markets has slowed or stopped completely. Materials supplies will soon be affected. Construction projects will most likely experience delays. Product shortages, delivery delays and shutdowns will drive up costs and extend project schedules.

Projects in planning may be canceled due to drop in demand, decline in capital or slowdown in economy. Retail stores may cancel expansion, educational facilities may delay starting new construction, transportation facilities may postpone later phases of long planned growth.

As I sit here writing this, the city of Boston this morning announced that ALL non-essential construction projects are to shut down today. That’s nearly all projects. Boston accounts for $22 billion/year in construction spending, 80% of all construction in the state of Massachusetts, 60% of all work in MA-CT-RI, 50% of all New England. This affects well over 100,000 jobs.

Also, the San Francisco Bay area has been directed to shelter-in-place, essentially shutting down all nonessential construction work. This impacts approximately 200,000 construction jobs and amounts to about double the volume of work as Boston.

We can expect more locations to issue directives such as these in the near future.

How Can We Measure the Effects Due to Covid-19 Impacts?

Let’s first establish the baseline. The starting baseline is my current construction spending and backlog forecast for 2020-2021 which includes 2019 total spending and new construction starts through February. There is considerable strength in Nonresidential Buildings and Non-building Infrastructure starts and spending. There is weakness in residential.

The best indicator of future construction activity is the sum of the projected monthly cash flows generated by all the construction starts that have been recorded.

This plot shows the correlation between projected cash flow from starts and actual spending.

Recession What If? Starting Baseline

To begin, we can look at the current forecast of new starts, backlog and spending.

Construction Starts in 2018 were up 4% and prior to that were up 10%/yr. 2019 starts including revisions are up 4%. 2020 starts are forecast down 4%. Current Backlog is up 30% in the last 4 years, at all-time high. Although spending is forecast up only 4%/yr. the next two years, spending is at an all-time high.

Residential construction starts peaked in 2018. Starts in 2019 are level yoy, but have been flat or in moderate decline since mid-2018. Spending is forecast up 5% in 2020 but down 1% in 2021.

Nonresidential Buildings starting backlog increased 10%/year for the 4 years 2017-2020. Starts have moved sideways or in slight decline since mid-2018. 2019 starts are down 9% from 2018. Spending is forecast up 3% in 2020 and 2021.

Infrastructure starting backlog, by far the most robust, has increased 15%/year for the 3 years 2018-2020. Spending is forecast up 6% in 2020 and up 8% in 2021.

It is important to understand when spending from backlog occurs. Average cash flow curves for nonresidential work show about 15%-20% of spending from new starts occurs in the year started and about 40%-50% occurs the following year. 80% of all nonresidential spending in any given year is from backlog. If new starts drop by 10%, that has only a 1.5% to 2% impact on total spending in the first year. The following year spending would be down 4% to 5%.

Residential spending is far more dependent on new starts than backlog. Only about 30% of residential spending comes from backlog and 70% from new starts. If residential new starts drop 10% that impacts total spending by 7% in that year.

Recession Scenario

When a recession occurs, new construction starts would be substantially reduced. Although some projects will be canceled or delayed mid-schedule, most projects already in construction would move on to completion. Most of the cut back comes from a reduction in new starts.

In the great recession, residential starts dropped 70% from 2005 to 2009, down from $400 billion to $110 billion. Nonresidential Buildings starts dropped 35% from 2008 to 2010. Nonbuilding starts fell only 6% in 2009. Total All Spending declined 30% from $1.160 trillion in 2006 to $788 billion in 2011.

Regardless what may lead to a construction recession, in this case a global pandemic, it is the current high amount of work in backlog that will work hard to mute its effect.

No analyst had been indicating huge declines in new construction starts within the next few years. At worst, some suggested a moderate slowdown. Prior to today, data seemed to agree with a moderate slowdown.

Although Dodge is forecasting the $ value of housing starts down 6% in 2020, Housing Starts # of units as reported by US Census in Q4 2019 are at a post-recession high, reducing the likelihood of such a decline.

Dodge 2020 forecast for new nonresidential buildings starts is down 2.5%.

This recession scenario does not assume a catastrophic failure of the economy.

It is unknown how much existing or new work might get canceled. To get an idea how a recession might impact construction spending, this analysis reduces new construction starts by 20% in 2020 and 10% in 2021 from the baseline. That’s about the average of what occurred in the great recession, although then it was far greater in residential and much less in non-building infrastructure. Only once in the last 20 years, other than the great recession, did new construction starts drop more than 5% in any sector in a year.

So initially, compared to the baseline forecast, there would be 20% less work to bid on in 2020 and 10% less in 2021. But that is not how spending, or revenues, would react. Backlog and spending schedule curves determine the impact on spending, or revenues.

Here’s the resulting change in the spending plots. Only the estimated spending to the right of the dateline changes.

Residential construction spending would drop about 14% in 2020 and then drop 13% in 2021 below the baseline scenario. Residential is far more dependent on new starts within the year for spending than on backlog. That’s why residential spending drops quicker than all other work.

Nonresidential Buildings spending ends 2020 4% lower than it would have under the baseline scenario but then drops 12% in 2021 and 10% in 2022. Backlog going into 2020 in this sector is strong and therefore, even though spending is 4% lower than baseline, 2020 still posts a spending gain of 1.5%. 2021 declines 8% and 2022 gains 1%.

Non-building Infrastructure spending ends 2020 3% lower than it would have under the baseline scenario but then drops 9% in 2021 and 10% in 2022. Non-building Infrastructure has so much work in backlog that this sector still posts a spending gain of 6% in 2020 and 1% in 2021. It declines by 2% in 2022.

The major declines in 2020 are residential since most residential spending comes from new starts within the year, but for all other work, the strength of backlog going into 2020 pushes most of the declines out to 2021 and 2022.

Total all spending would drop from the current 2020 forecast of $1.365 trillion to $1.260 trillion. In 2021 and 2022, instead of baseline spending of $1,370 trillion, it would drop to $1.230, back to the level of 2016. The losses in the Great Recession, a total drop of almost $400 billion, set construction spending growth back 12 years.

Not only did Boston shut down non-essential construction projects but also New York and California have done the same. Boston accounts for about $20 billion/year in construction spending, but NY and CA together account for about $280 billion. Let’s assume CA and NY and Boston shut down all but critically essential construction for 1 month. Let’s say that is 80% of all construction. That represents a shutdown of $20 billion of construction in one month’s time.

The difference with temporary shutdowns vs a reduction in new starts is that work shut down is delayed. It will reduce total spending in that month in 2020 but will shift the entire schedule of spending out by some number of months. Upon resuming, some will still occur in 2020, and some very likely gets pushed into 2021 or later, but eventually all of the delayed work will get completed. If 20% of all U.S. construction shut down for one month it would delay $25 billion worth of work by one month. If 20% of all 2020 U.S. construction new starts get canceled, it would reduce future workload by $250 billion, spread over the next three years.

The magnitude of spending declines would impact the jobs situation. History shows that job declines of the same magnitude do not follow immediately with volume declines, therefore we would not see an equivalent reduction in workforce in 2020. But spending declines in 2021 and 2022 could lead to a loss of about 500,000 to 750,000 jobs. Over the course of the great recession we lost 2.3 million jobs.

You can read more about the job situation here.

To summarize:

This is a WHAT IF? Analysis.

Assumption that new construction starts drop 20% in 2020 and 10% in 2021 lower than the baseline forecast.

This would cause total construction spending to drop 8% in 2020, 12% in 2021 and 7% in 2022 from the previously established baseline forecast.

The spending declines measured in dollars, measured from the previously established baseline forecast, are: down $100 billion in 2020, down $140 billion in 2021 and down $100 billion in 2022.

This could lead to a loss of about 500,000 to 750,000 jobs for three years.

What this will do to the construction inflation rate is hard to predict. Typically when work volume decreases the bidding environment gets more competitive and prices go down. However, if materials shortages develop, that would cause prices to increase. Add to these issues the fact that almost every project currently under construction may be halted for a period of time, the delays may add several weeks to perhaps a month or two to the overall schedule. I think in this case the materials availability issues and schedule delays will outweigh any decline in work available for bid. I would add a minimum of 1% to all baseline inflation rates for 2020 and 2021.

“None of us have much of a sense what the economy will be in 2021.” Fed Chair Jerome Powell 12-11-19

See Also Pandemic Impact on Construction – Part 2 3-31-20

See Also Pandemic Impacts – Part 3 – Jobs Lost, Inflationary Cost 4-9-20

2020 Construction Economic Forecast – Jan 2020

Construction Analytics 2020 Construction Economic Forecast

This January, 2020 Construction Economic Forecast addresses New Construction Starts, Inflation, Cash Flow or distribution of construction work over time, Backlog, Spending or Revenue, and Volume. New Construction Starts is new work entering Backlog. Cash Flow gives the pattern of Spending. Spending adjusted for Inflation differentiates between Revenue and Volume. Backlog can be referenced to assess expected future Volume and Spending. Cash flow provides an indication of when Volume occurs or in what year Revenues occur.

Starts data is from Dodge Data & Analytics. Spending data is from the U.S. Census Bureau. Jobs data is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Inflation data is from the source labeled. Cash flow, Backlog and Inflation forecast data are developed internally. All data in this report is national level data. All forecast data is by Construction Analytics

Click here for a downloadable PDF of 2020 Construction Economic Forecast Feb 2020

Click here for a downloadable PDF of SUMMARY – 2020 Construct Econ Forecast 2020

Summary of 2020 Construction Outlook

Total of All construction spending in 2019 is forecast to decrease -0.2% to $1.305 trillion. For 2020, spending increases by 4.6% to $1.365 trillion.

Nonresidential Buildings construction spending is forecast to finish 2019 at $455 billion, level with 2018. For 2020 the forecast is a gain of 3% to $467 billion. Educational and Commercial/Retail held down gains in 2019. Office (which includes data centers) and Lodging gained 7% each. Office, Healthcare and Educational all support growth in 2020.

Residential construction spending forecast is down 5% to $521 billion in 2019 and up 6% to $552 billion in 2020. New starts are recovering from a 10% drop in the 1st half of 2019 and are now expected down only slightly for 2019 after the latest three-month average starts were the highest ever. Residential spending peaked in Q1 2018 and dropped 11% to a low in July 2019. Although spending has since recovered half of that drop, growth in 2019 slowed to less than inflation. Residential construction volume in 2019 dropped 8%, the largest volume decline in 10 years. 2020 volume is forecast to increase 2%.

Non-building Infrastructure construction spending is forecast to increase 7% to $329 billion in 2019 and 5% to $345 billion in 2020. Transportation spending gets strong growth from three years of record new starts. Half of all transportation spending in 2021 comes from projects that started in 2017-2019. Both Public Works and Highway starts have been increasing modestly to reach new highs in 2019. Non-building Infrastructure projects have the highest share of multi-billion dollar projects that spread spending out over longer duration.

Spending data for the previous two years gets revised in July of the following year. Those revisions are always up, although some markets may increase while others decrease. So, even though the current forecast for 2019 spending is down -0.2% to $1.305 trillion, that will most likely increase to a net gain.

In their October annual report, Dodge Data forecast 2019 construction starts to total $809 billion, down 1% from 2018. However, starts are always revised up in the following year. In just the last three years, nonresidential starts have been revised up by 7.5%/yr and residential starts by 2.4%/yr. I expect revisions will show 2019 starts increased by 3% to 4% over 2018. However, even with revisions, 2019 starts will post the slowest annual growth since 2011.

Dodge Data and Analytics new construction starts for November 2019 advanced to the highest seasonally adjusted annual rate ever, resulting in the three months Sep-Oct-Nov 2019 posting the highest 3-mo average ever, 10% higher than the total average for 2018. Several long duration projects started, so a lot of the spending from these new starts will occur in 2021-2022. Dodge is forecasting 2020 starts down 4%. This forecast includes only 1% to 2% growth in new starts for 2021-2022.

Starting backlog, which increased 5% leading into 2020 is currently at an all-time high, up 20% since 2017. 80% of all Nonresidential spending within the year will be generated from projects in starting backlog. More than 20% of all spending in 2020 is from projects that started more than 3 years ago.

While a few markets will outperform in 2020 (transportation, public works, office), predicted cash flow (spending) from backlog is up only 1% to 2%. Long duration projects added to backlog and will spread spending out over the next few years. Current indications are that 2020 backlog will be up 4% for residential work, 6% for nonresidential buildings and 7% for infrastructure work.

- Starts increased 8%/yr. in 2016 and 2017, but only 4% in 2018.

- Starts are forecast to decline slightly in 2019 and 2020.

- Spending increased 9%/yr. from 2012 to 2016, then slowed to 4%/yr. in 2017 and 2018.

- Spending declined 1% in 2019 and is forecast up 4% for 2020 and 1% in 2021.

- Backlog reaches a post-recession high in 2020, up 20% from 2017, up 100% from 2013.

Since early 2018, jobs have been increasing while construction volume is declining. A declining volume of work does not support jobs growth. When volume of work decreases, jobs should also decrease. If jobs increase, then it results in more workers to produce the same amount of work. In other words, productivity is declining. This could result in one or more of these outcomes:

- Labor demand on hiring drives labor cost up by unexpected amounts.

- New labor coming into the workforce has less experience, lowering productivity.

- Contractors cannot meet schedules, extending project duration.

- Contractors work overtime to meet schedules, adding cost.

All scenarios either extend project duration or drive up the cost of projects or both, which could lead to some unforeseen inflation.

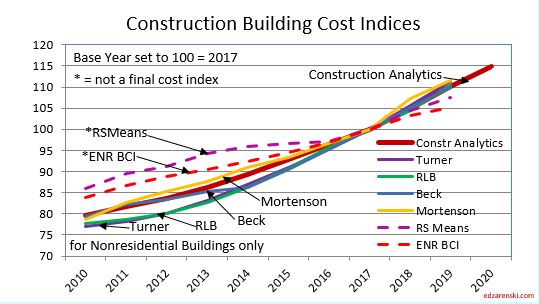

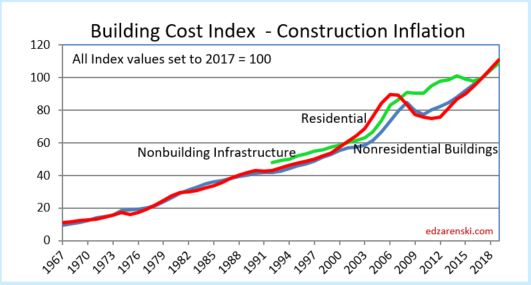

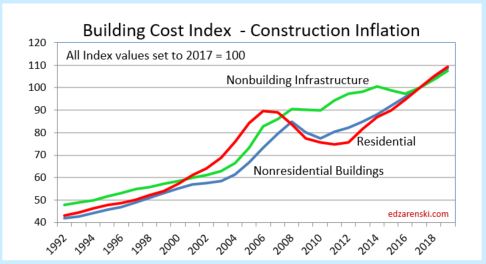

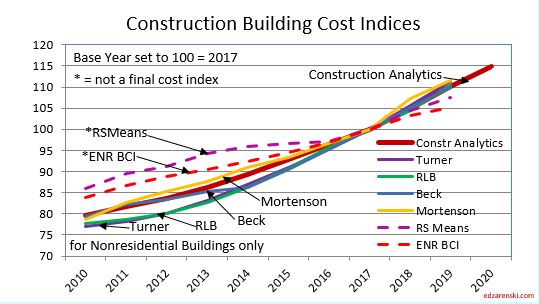

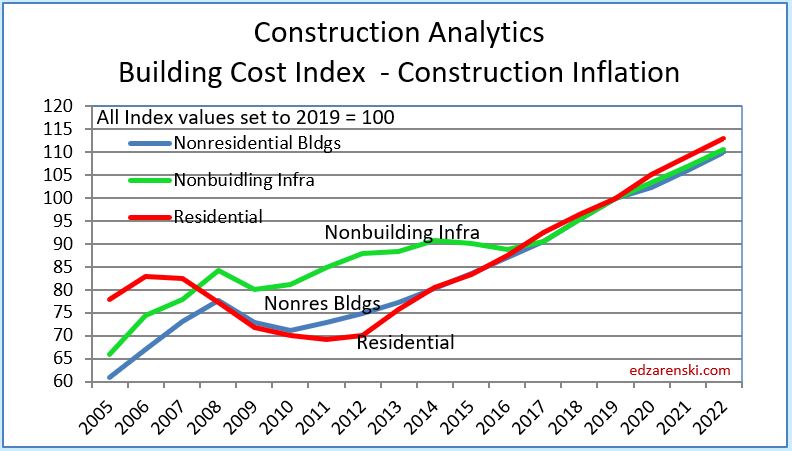

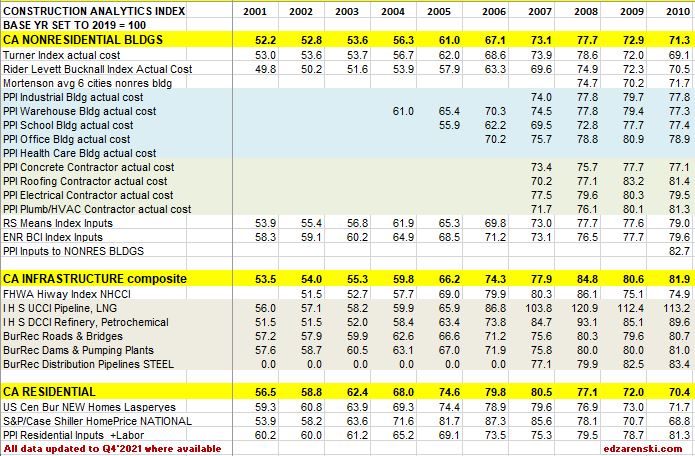

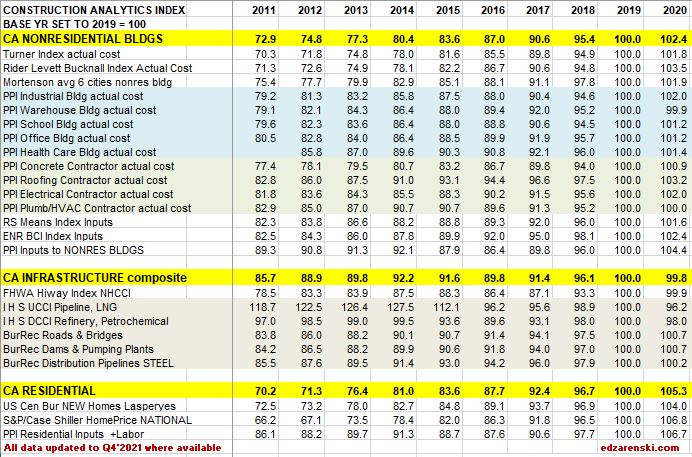

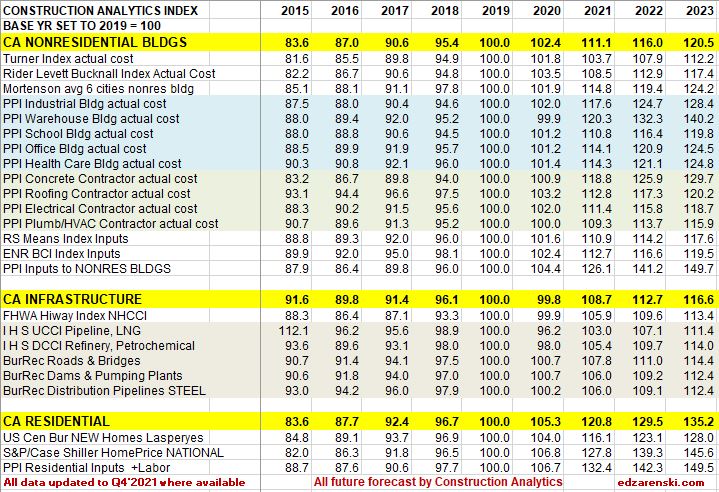

General construction cost indices and input price indices that don’t track whole building final cost do not capture the full cost of inflation on construction projects. Residential and Nonresidential Buildings inflation indices developed by Construction Analytics are final cost selling price indices.

Nonresidential buildings inflation, after hitting 5% in both 2018 and 2019, is forecast for the next three years to fall from 4.4% to 3.8%, lower than the 4.5% average for the last 4 years.

Residential construction inflation in 2019 was only 3.6%. However, the average inflation for six years from 2013 to 2018 was 5.5%. It peaked at 8% in 2013 but dropped to 4.3% in 2018 and only 3.6% in 2019. Forecast residential inflation for the next three years is level at 3.8%.

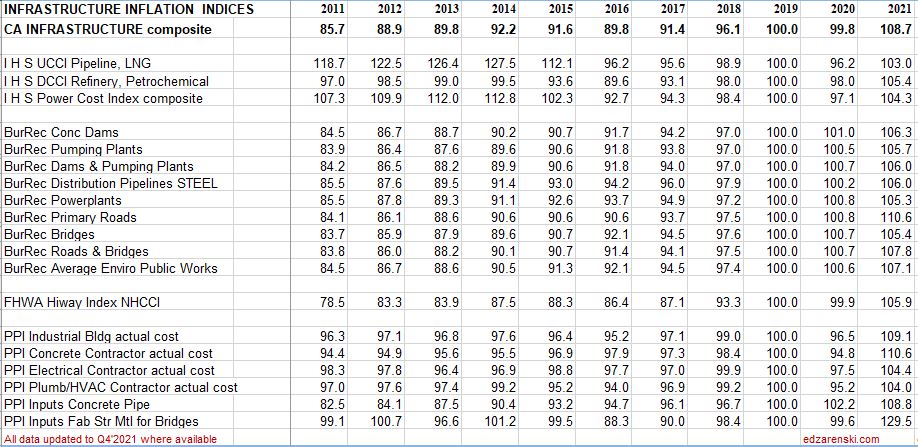

Non-building infrastructure indices are so unique to the type of work that individual specific infrastructure indices must be used to adjust cost of work.

This link points to comprehensive coverage of the topic inflation. Click Here for Link to a 20-year Table of 25 Indices

This link points to articles related to the Construction Outlook for 2020. Click Here for Link to Construction Economic Outlook 2020

Some Signs Ahead – Economic Indicators

The following reports can be accessed by clicking on the hyperlinks provided.

AIA Consensus January 2020 Construction Forecast is a semi-annual survey of construction economists’ projections for future nonresidential buildings spending. The January 2020 Consensus report of expectations for nonresidential construction shows predicted growth for 2020 at 1.5%. All major markets show growth expectations between -2% and +4%. Office, Healthcare and Education are projected to gain 3% to 3.9%. Commercial/Retail, Lodging and Amusement/Recreation are expected to fall 1.3%-1.9%.

Architectural Billings Index (ABI) measures monthly work on the boards in architectural

firms. It is a nine to twelve month leading indicator to construction. Index values above 50 show increasing billing revenues, and below 50 indicates declining revenues. All ABI indices were above 50 from Jan. 2017 through Jan. 2019. However, from Jan. 2018 through 2019, contrary to the index, spending posted the largest drop in six years.

Dodge Momentum Index (DMI) is a monthly measure of nonresidential projects in

planning, excluding manufacturing and infrastructure. It is a leading indicator of specific nonresidential construction spending by approximately 12 to 15 months. This plot moves the DMI ahead to show when the index would have an affect on construction spending. The DMI is indicating a slow decline in new spending for the 1st half of 2020 but then a rapid increase in the 2nd half. From July 2019 onward, the DMI does not agree with the Starts Cash Flow which is a forecast of the movement in the spending forecast.

Producer Price Index indices for 2019 materials average Inputs to construction in 2019 posted a gain of only 1.5%. up 2.1% for nonresidential buildings and up only 0.9% for residential. However, selling price indices for nonresidential buildings and nonresidential trades averages 4% with Industrial buildings, warehouses and schools all over 4.5%. The difference between these indices is the combined affect of labor cost and contractor margins which are not tracked in the PPI inputs.

FMI Q4 2019 Nonresidential Construction Index (NRCI) is 50.4, the lowest reading in eight years. The NCRI is a diffusion index based on a survey of opinions submitted by nonresidential construction executives. With only one slight bump up in Q2 2019, it dropped every other quarter since Q2 2018. Construction spending has been lower every quarter since Q2 2018. Construction spending in 2018 and 2019 declined to the two lowest years since 2011.

Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Non-Manufacturing Index (NMI) Report

for December 2019 is a better indicator of activity in the construction industry than the

ISM manufacturing report. The NMI measures economic activity in 13 industries

(including construction) not covered in the manufacturing sector. The December NMI is

55.0, above 50 for 126 consecutive months, indicating continued economic growth.

Construction shows growth in business activity and increased backlog. Construction shows slower deliveries but no change in prices paid. Construction reports contractors in short supply. A comment from a construction respondent, “While demand is outstripping supply in the housing market, business is down due to global trade insecurity causing affordability, labor and cost pressures.”

Construction Starts > Cashflow > Backlog > Spending

One of the best predictors of construction inflation is the level of activity in an area. When the activity level is low, contractors are all competing for a smaller amount of work and therefore they may reduce bids. When activity is high, there is a greater opportunity to bid on more work and bids can be higher. The level of activity has a direct impact on inflation.

Construction starts data is needed to predict spending or the level of market activity. This provides insight into market costs and inflation. To predict spending activity from new construction starts, the starts data must be spread over time using appropriate cash flow curves. On average about 20% of new construction starts gets spent within the year started, 50% is spent in the next year and 30% is spent in year three or later. Applying an expected duration for all starts depending on market type to produce a forecast cash flow from starts data, the expected pattern of spending is developed.

The starts data is a survey. As in any survey, starts data captures a share of the total market or a portion of all construction spending, on average about 60% of all construction. The easiest way to understand this is to compare total annual construction starts to total annual spending. National starts from 2016 to 2019 range from $750 billion/year to $800 billion/year, while spending in this period ranges from $1,200 billion/year to $1,300 billion/year. From this comparison we can see starts captures a share of about 60% of the total market.

This table shows Office starts in 2016 did not drive up spending in 2017, the 2nd year, when most spending occurs. Manufacturing had two huge years of growth in starts but very little growth in spending the following years. The cash flow curves for starts determine when spending occurs. The forecast shows Office spending up 9% in 2020 and Manufacturing up 10% in 2021.

All construction starts data in this report references Dodge Data & Analytics Starts Data.

Backlog at the beginning of the year or new starts within the year does not give an indication of spending within the year. New starts within any given year could contribute spending spread out over several years. Total cash flow in the year, or spending, could include cash flow from projects that started or entered backlog years ago. An increase in backlog could represent a level rate of market activity, but for a longer duration.

Cash flow provides the best indicator of how much and when spending will occur. Cash flow from all previous starts gives a prediction of how spending will change monthly from all projects in backlog. Cash flow totals of all jobs can vary considerably from month to month, are not only driven by new jobs starting but also old jobs ending, and are heavily dependent on the type, size and duration of jobs.

New Construction Starts

Total of all construction starts increased every year from 2010 through 2019. Average growth from 2012 to 2017 was 8%/year. New starts slowed to +2% in 2018 and are forecast up +1% in 2019 and +2% in 2020. Backlog is still up leading into 2020 but after that starts and backlog are forecast to remain below 2% gain or decline over the next few years. Total spending has only slight gains in 2021 and 2022.

Nonresidential Buildings starts (excluding Terminals) increased every year since 2010. Only Manufacturing declined slightly in 2017. Commercial/Retail declined 6% in 2018. Commercial, Lodging and Amusement posted declines in 2019. The last three years (adjusted) starts are up only 2% to 3% per year.

Backlog for Office Buildings and Lodging is up 100%+ since 2016. Office includes data centers. Commercial/Retail backlog is down 14% in the last two years. Spending is still up 4% in 2020 but then with the slowdown in starts forecast in 2020, backlog growth stalls and spending slows in 2021-2022.

75%-80% of all Nonresidential Buildings spending within the year will be generated from projects that were booked in starting backlog at the beginning of the year.

Non-building Infrastructure two markets with the largest share of new starts are Highway/Bridge and Transportation. Transportation terminals and rail starts are up 35% in the last three years, but backlog has doubled because a large portion of those starts is very long duration projects.

Non-building Infrastructure starts can be erratic with a long pattern of up then down years. Starts (including Terminals) gained only 4% in 2019 but are at an all-time high. Even though starts gain less than 2% in 2020, backlog peaks in 2021. Spending increases are in the 5% to 8% range at least for the next two years. Infrastructure projects typically have the longest duration. Projects contribute spending sometimes up to 5 or 6 years. Spending in recent years has been boosted by Transportation terminals and Highway projects.

Most of the residential spending in any year is cash flow from new starts. For short duration residential spending, single-family residential and renovations work, approximately 75% of spending in the year comes from project starts within the year.

For long duration residential spending, typical of multifamily residential, approximately 50%-55% of the spending occurs in the year of the start, 35%-40% in the next year and only 5%-10% occurs two years out.

- 75% to 80% of short duration Residential spending within the year will be generated from projects that are recorded as new starts within the year.

- 50% to 55% of long duration Multifamily Residential spending within the year will be generated from projects that are recorded as new starts within the year.

Dodge releases its first forecast of next year’s starts every year in the 4th quarter. Dodge initial forecast for 2019 starts was $808 billion, no change from 2018. Starts are currently at $818 billion and will be subject to more revisions.

- Previous year starts always later get revised upwards. Therefore, current year starts YTD growth is always understated. This analysis compensates for that.

- New starts will generate record high starting backlog for every sector in 2020.

Revisions for the last 8 years averaged more than +6%/yr., with most of the upward revision in nonresidential buildings. However, for the last 3 years revisions added only 4%. Revisions to nonresidential buildings have been greater than 7%/year for the last 3 years, non-building revisions average 8%/yr and residential revisions average 2.4%/yr. Therefore, 2019 starts growth is very likely under-reported.

For nonresidential buildings spending, long duration jobs can sometimes have a 5 to 6-year schedule. On average most years have at least some projects start that will be under construction for at least 4 years. For an entire year’s worth of starts, approximately 20% of the spending occurs in the year started, 50% in the next year, 25% in the third year and only 5% in the fourth year or later year. Residential starts contribute spending into the third year. This means that nonresidential spending growth in 2019 was affected by starts from 2016 and residential growth from starts in 2017. This also means that nonresidential spending growth in 2020 is still being affected by starts from 2017.

The Estimated Spending plot below is an index. The plot shows greater accuracy in the cash flow forecast when the slope of the predicted cash flow and actual spending plot lines move in the same direction at the same slope. It’s not the spread between the lines that gives any indication. If the slope of the lines is the same, then the cash flow is accurately predicting the spending.

The light green line for nonresidential buildings spending estimated from starts cash flow shows smooth spending, even though actual monthly starts can be erratic. The actual spending often follows close to the pattern estimated from cash flows.

Starts are sometimes misinterpreted in common industry forecasting articles. Starts dollar values represent a survey of about 60% of industry activity, therefore Starts dollar values cannot ever be used directly to indicate the volume of spending. Also, Starts do not directly indicate changes in spending per month or per year. Only by including an expected duration for all Starts and producing a forecast Cash Flow from Starts data can the expected pattern of spending be developed. Finally, it is the rate of change in Starts Cash Flows that gives an indication of the rate of change in spending.

Starting Backlog

Starting Backlog is the Estimate-to-Complete (ETC) value of all projects under contract at the beginning of a period. Projects in starting backlog could have started last month or last year or several years ago.

- 75%-80% of all Nonresidential Buildings spending within the year will be generated from projects in starting backlog.

- 80%-85% of all Non-Building Infrastructure spending within the year will be generated from projects in starting backlog.

- 70% of All Residential spending within the year is generated from new starts, but this is weighted because 85% of all residential work is short duration single family and renovation work.

- 65% on long duration Multifamily Residential spending within the year will be generated from projects in starting backlog.

Nonresidential Buildings starting backlog at the beginning of 2020 reached an all-time high. For purposes of this analysis, I’ve set only moderate or low increases in starts for 2020 and 2021, so this forecast may hold down the future backlog and spending forecast. However, backlog leading into 2020 is up 60% in 5 years.

Non-building Infrastructure starting backlog at the beginning of 2020, up 10% from 2019, reached an all-time high. Some of this is very long-term work that started construction in 2016-2017 and it will contribute spending for the next several years. In fact, about half of all spending in 2020 comes from projects that started prior to Jan 2019. 2021 Backlog is forecast to increase 9%. Backlog is up 25% in the last 3 years.

Residential starting backlog, unlike nonresidential, does not contribute nearly as much short-term residential spending within the year. Multifamily residential has a longer duration and a greater percentage of spending comes from backlog. But, due to the shorter duration of projects, about 75% of single family and residential renovation spending within the year is generated from new starts.

The plot below shows that backlog has been increasing since 2011-2012. Many projects in backlog extend out several years in the schedule to support future spending, so backlog growth in not an indicator that tracks directly yr/yr with spending. Without any new construction starts in 2020 or beyond, current backlog at the start of 2020 would still contribute some spending for the next 6 years until all the projects in backlog are completed.

For Nonresidential Buildings, 68% of 2020 Backlog will get spent within the 1st year. 27% of 2020 Backlog will get spent next year. 2020 backlog will last for 58 months.

For Non-building Infrastructure, 53% of 2020 Backlog will get spent within the 1st year. 32% of 2020 Backlog will get spent next year. 2020 starting backlog will last for 72 months

For Residential construction, 95% of 2020 Backlog will get spent within the 1st year. 2020 backlog would run out in 18 months. Residential construction is far more dependent on new construction starts. If no new work started, the backlog workload would run out quickly.

How much of the spending forecast is supported by starting backlog. For all construction, 62% of 2020 total spending comes from starting backlog. If no new work starts after December 2019, then only 24% of the 2021 spending forecast would be supported from 2020 starting backlog.

Cash Flow

Simply referencing total new starts or backlog does not give an indication of spending within the next calendar year. Projects, from start to completion, can have significantly different duration. Whereas a residential project may have a duration of 6 to 12 months, an office building could have a duration of 18 to 24 months and a billion-dollar infrastructure project could have a duration of 3 to 4 years. New starts within any given year could contribute spending spread out over several years. Cash flow totals of all jobs can vary considerably from month to month, are not only driven by new jobs starting but also by old jobs ending, and are heavily dependent on the type, size and duration of jobs.

Cash flow from all previous starts still in backlog plus cash flow from new starts supports a 2020 spending forecast of $1,365 billion, an increase of 4.6% over 2019. Dodge initial November 2019 forecast for construction starts in 2020 is $776 billion, down 4% from 2019. However, subsequent revisions may increase that a few percent.

There are sometimes vast differences between amounts of Starts, whether already in Backlog at beginning of year or New Starts within the year, and Cash Flow from Backlog and New Starts. The highlighted examples below, Office and Manufacturing, show starts is not a good indicator of expectation for spending.

Note that new manufacturing starts were up 29% in 2017 and 26% in 2018, yet 2019-2020 spending is forecast to increase only 3%. This is due in part to the share of market captured in the starts survey having increased, but also to very large projects that started but that have much longer than normal duration to complete, therefore moving the largest monthly cash flows further out into the future.

The following table clearly shows there is not a correlation between starts in any year with spending in either the current or the following year. The practice of using construction starts directly to predict spending can be very misleading in an industry that relies on data for predictive analysis to plan the future. Not only does it not predict the volume of spending in the following year, it does not even consistently predict the direction spending will take, up or down, in the following year. It’s a false indicator and it’s not a good use of data.

Spending

Total of All construction spending is forecast to increase 0.2% to $1.305 trillion in 2019, 4.6% to $1.365 trillion in 2020 and 0.9% to $1.377 trillion in 2021.

Construction spending is strongly influenced by the pattern of continuing or ending cash flows from the previous two to three years of construction starts. Current month/month, year/year or year-to-date trends in starts often do not indicate the immediate trend in spending.

Residential Buildings Spending

Residential construction spending is forecast down -4.6% to $521 billion in 2019, but strong new starts in Q4 increases spending by 6.0% to $552 billion in 2020. A 5% decline in 2020 new starts lowers spending in 2021 by -3.79% to $532 billion.

New starts are recovering from a 10% drop in the 1st half of 2019 and are now expected down only slightly for 2019 after the latest three-month average starts were the highest ever. Residential monthly rate of spending peaked in Q1 2018 and dropped 11% to a low in July 2019. Although spending has since recovered half of that drop, there was no overall growth in 2019.

Residential spending average growth from 2011 through 2017 was 12%/year. Although spending increased 2.7% in 2018, growth was less than inflation of 4.3%, therefore 2018 volume after inflation decline by 1.5%. In 2019 residential spending decreased 4.5%. After accounting for 3.6% inflation, real volume decreased by 7.8%. Residential construction volume in 2019 posted the largest volume decline in 10 years. 2020 volume is forecast to increase only 2%.

Single Family Residential spending is more dependent on new starts within the most recent 12 months than on backlog from previous starts. Multi-Family Residential spending is more dependent on backlog.

Total residential new starts for the last 3 months and the last 6 months posted the highest rates of growth since 2006. Growth for 2019 is initially down -2.5%, but that is because 2018 has already been revised up by 2.1% and 2019 is yet to be revised. Revisions are usually up. Dodge predicted 2019 starts would fall 5%, however my current forecast is a drop of only 1.3%. 2020 starts are forecast up 2.6%.

Residential current$ spending reached a 12-year high in 2018 of $580 billion but that was still far below the 2006 peak of $690 billion. In constant$, adjusted for inflation, all years from 1998 through 2007 were higher than 2018. In constant$, 2018 spending is still 28% below the 2005 peak. As of Dec 2019, constant$ spending is 37% below the 2005 peak.

Nonresidential Buildings Spending

Nonresidential Buildings construction spending for 2019 is forecast to finish at $455 billion, up only 0.3% from 2018. Spending is forecast to increase 2.9% to $467 billion in 2020 and 1.2% to $473 billion in 2021. Healthcare, Educational and Office (which includes data centers), support the 2020 forecast. There is downward pressure the next two years from slowdowns in Amusement/Recreation, Commercial/Retail and Lodging.

Current$ spending for Nonresidential buildings reached a monthly high of $470 billion in mid-2018 but then fell slightly and remained between $450 and $460 billion in 2019. Both 2018 and 2019 totals averaged new annual high marks just slightly above 2008. Average annual 2019 spending grew only 0.3% from 2018. 2020 is forecast up 2.9%.

Spending in constant$ (inflation adjusted $) peaked in mid-2018 at $450 billion but by Dec. 2019 it’s down 10% to only $406 billion. It’s expected to remain at this level throughout 2020. Constant $ spending or real volume growth shows all years from 1995 through 2010 had higher volume than the 2020 forecast.

Non-building Infrastructure Spending

Non-building Infrastructure construction spending is forecast to increase 6.8% to $329 billion in 2019 and 4.9% to $345 billion in 2020. Transportation spending gets strong growth from three years of record new starts. In 2017, transportation terminals increased more than 100%. Half of all transportation spending in 2021 comes from projects that started in 2017-2019. Both Public Works and Highway starts have been increasing modestly to reach new highs in 2019. Non-building Infrastructure projects have the highest share of multi-billion dollar projects that spread spending out over longer duration.

Current infrastructure backlog is at an all-time high and spending is expected to follow the increased cash flows from the elevated backlog. Transportation terminals new starts jumped 100%+ in 2017 . Starting backlog for all transportation work is the highest ever, up 100% since 2017. Transportation spending is projected to increase 20-25%/year for the next two years.

Current$ spending for Non-building Infrastructure reached a high annual rate of $340 billion in mid-2019 but then fell slightly to only $325 billion by year end. Spending in 2020 is expected to increase slowly from $330 billion to $350 billion. Total 2020 spending is expected to increase 5%.

Non-building Infrastructure construction spending in constant $ (inflation adjusted $) peaked at reached $330 billion in 2016, an all-time high, but then dropped to $280 billion in 2018. In 2020 it will average $300 billion. Constant $ spending or real volume growth dropped 10% in 2017-2018 but is forecast to gain 6% in 2019-2021.

Public Infrastructure and Public Institutional

Just 60% of all Non-building Infrastructure spending, about $194 billion, is publicly funded. That public subset of work averages growth of less than $10 billion/year.

About 30% of all Nonresidential Buildings spending, about $134 billion, is publicly funded, mostly Educational. Nonresidential buildings spending makes up just over 40% of Public spending.

- Infrastructure = $328 billion, ~25% of all construction spending.

- Infrastructure is about 60% public, 40% private. In 2005 it was 70% public.

- Public Infrastructure = $194 billion. Private Infrastructure = $134 billion.

- Power and Communications are mostly privately funded infrastructure.

- Nonresidential Buildings is 30% public (mostly institutional), 70% private.

- Educational, Healthcare and Public Safety are Public Nonres Institutional Bldgs

- Public Commercial construction is not included.

- Public Institutional = $110 billion, mostly Education ($80b).

Public Infrastructure + Public Institutional = $300 billion, 23% of total construction spending.

Public Infrastructure + Institutional average growth is $12 billion/year. It has never exceeded $30 billion in growth in a single year.

See also Publicly Funded Construction

See also Down the Infrastructure Rabbit Hole

The two largest markets contributing to public spending are Highway/Bridge (33% of total public spending) and Educational (27%), together accounting for 60% of all public construction spending. At #3, Transportation is only 13% of public spending. Environmental Public Works combined makes up 17% of public spending, but that consists of three markets, Sewage/Waste Water, Water Supply and Conservation. Office, Healthcare, Public Safety and Amusement/Recreation account for about 3%-4% each.

Highway is 100% public and Public Works 99%. Educational is 80% public, Transportation 70%, Amusement/Rec 50% and Healthcare 20%.

Public Starts and Backlog

The Public markets with the largest share of growth in new starts the last two years are Transportation and Public Works. Transportation terminals and rail starts are up 30% in the last three years, but backlog has doubled because a large portion of those starts is very long duration projects. Public works starts are up 20% and backlog is up 40%. Infrastructure projects typically have the longest duration. Projects contribute spending sometimes up to 5 or 6 years.

Public spending backlog is up an average 9%/year for the last three years. Some of this is very long-term work that started construction in 2016-2017 and it will contribute spending for the next several years. 40% of all public spending in 2020 comes from projects that started prior to Jan 2019. Backlog is up 25% in the last 3 years and is forecast to increase another 9% to start 2021.

Public Spending

Total public spending for 2019 is projected to finished up 8% at $332 billion. Every major public market is projected to finish up in 2020. By far, the largest Public spending increases measured in dollars for 2020 are Transportation, Highway and Educational.

Public work construction spending in constant $ (inflation adjusted $) reached $318 billion in 2016, short of the highs reached in 2002 and 2008. Constant$ value work then dropped to $300 billion in 2017 and has been level through 2019. In 2020 it will increase only 1%.

Construction Inflation

The level of construction activity has a direct influence on labor and material demand and margins and therefore on construction inflation.

Nonresidential buildings inflation, after hitting 5% in both 2018 and 2019, is forecast for the next three years to fall from 4.4% to 3.8%, lower than the 4.5% average for the last 4 years.

Residential construction inflation in 2019 was only 3.6%. However, the average inflation for six years from 2013 to 2018 was 5.5%. It peaked at 8% in 2013 but dropped to 4.3% in 2018 and only 3.6% in 2019. Forecast residential inflation for the next three years is level at 3.8%.

Nonresidential Buildings and Non-building Infrastructure backlog are both at all-time highs. 75% to 80% of all nonresidential spending within the year comes from starting backlog. Most spending for residential comes from new starts in the year.

2020 starting backlog is up 5.5% across all sectors. However, while a few markets will outperform in 2020 (transportation, public works, office), predicted cash flow (spending) from backlog is up only 1% to 2%. Long duration projects added to backlog and will spread spending out over the next few years.

Residential new construction starts in 2019 (number of units started) gained 4% over 2018. In 2018, starts dropped every quarter after Q1, but then increased every quarter in 2019 and closed out the 2nd half of 2019 at 9% higher than the average of the previous six quarters. New starts measured in dollars dropped slightly in 2019. Spending from new starts fell 5% in 2019 but is forecast up 6% for 2020. Residential construction volume (spending after inflation) in 2019 dropped 8%, the largest volume decline in 10 years. Volume in 2019 dropped to a 4-year low. A volume gain of 2% in 2020 leaves residential still at a 4-year low.

General construction cost indices and Input price indices that don’t track whole building final cost do not capture the full cost of inflation on construction projects.

To differentiate between Revenue and Volume you must use actual final cost indices, otherwise known as selling price indices, to properly adjust the cost of construction over time.

Selling Price is whole building actual final cost. Selling price indices track the final cost of construction, which includes, in addition to costs of labor and materials and sales/use taxes, general contractor and sub-contractor margins or overhead and profit.

Consumer Price Index (CPI), tracks changes in the prices paid by consumers for a representative basket of goods and services, including food, transportation, medical care, apparel, recreation, housing. This index in not related at all to construction and should not be used to adjust construction pricing.

Producer Price Index (PPI) for Construction Inputs is an example of a commonly referenced construction cost index that does not represent whole building costs. Engineering News Record Building Cost Index (ENRBCI) and RSMeans Cost Index are examples of commonly used indices that do not capture whole building cost.

Producer Price Index (PPI) Material Inputs (which excludes labor and margins) to new construction increased +4% in 2018 after a downward trend from +5% in 2011 led to decreased cost of -3% in 2015, the only negative cost for inputs in the past 20 years. Input costs to nonresidential structures in 2017+2018 average +4.3%, the highest in seven years. Infrastructure and industrial inputs were the highest, near 5%. But input costs for 2019 are coming in at less than +1%. Material inputs accounts for only a portion of the final cost of constructed buildings.

Materials price input costs in 2019 slowed to an annual rate of less than 1%.

Labor input is currently experiencing cost increases. The National construction unemployment rate was recently posted below 4%, the lowest on record with data back to 2000. The average has been below 5% for the last 18 months. During the previous expansion it hit a low average of 5%. During the recession it went as high as 25%. An unemployment rate this low signifies a tight labor market. This may cause contractors to pay premiums over and above normal wage increases to keep valued workers from leaving. Some premiums accelerate labor cost inflation but are not recorded in published wage data, so aren’t easily tracked. Lack of experienced workers and premiums to keep labor drive labor cost increases higher than wage growth.

Although many contractors report shortages due to labor demand, labor growth may slow due to a forecast 2019-2020 construction volume decline. We might see a labor growth decline lag spending/volume decline.

When construction activity is increasing, total construction costs typically increase more rapidly than the net cost of labor and materials. In active markets overhead and profit margins increase in response to increased demand. These costs are captured only in Selling Price, or final cost indices.

Construction Analytics Building Cost Index, Turner Building Cost Index, Rider Levett Bucknall Cost Index and Mortenson Cost Index are all examples of whole building cost indices that measure final selling price (for nonresidential buildings only). The average annual growth for all these indices over the past five years is 4.7%/year. For the last two years, average nonresidential buildings inflation is 5.3%.

- Long-term construction cost inflation is normally about double consumer price index (CPI).

- Average long-term nonresidential buildings inflation excluding recession years is 4.2%.

- Average long-term (30 years) nonresidential construction cost inflation is 3.5% even with any/all recession years included.

- In times of rapid construction spending growth, nonresidential construction annual inflation averages about 8%. Residential has gone as high as 10%.

- Nonresidential buildings inflation has average 3.7% since the recession bottom in 2011. It has averaged 4.2% for the last 4 years.

- Residential buildings inflation reached a post-recession high of 8.0% in 2013 but dropped to 3.4% in 2015. It has averaged 5.8% for the last 5 years.

- Although inflation is affected by labor and material costs, a large part of the change in inflation is due to change in contractors/supplier margins.

- When construction volume increases rapidly, margins increase rapidly.

- Construction inflation can be very different from one major sector to the other and can vary from one market to another. It can even vary considerably from one material to another.

Residential construction inflation in 2019 was only 3.6%. However, the average inflation for six years from 2013 to 2018 was 5.5%. It peaked at 8% in 2013 but dropped to 4.3% in 2018 and only 3.6% in 2019. Residential construction volume in 2019 dropped 8%, the largest volume decline in 10 years. Typically, large declines in volume are accompanied by declines in inflation. Forecast residential inflation for the next three years is level at 3.8%.

A word about Hi-Rise Residential. Most of the cost of a hi-rise residential building would remain the same whether the building was for residential or nonresidential use. On the contrary, this type of construction is totally dis-similar to low-rise residential, which in large part is stick-built single family homes. Therefore, a more appropriate index to use for hi-rise residential construction is the nonresidential buildings index.

Nonresidential inflation, after hitting 5% in both 2018 and 2019, is forecast for the next three years to fall from 4.4% to 3.8%, lower than the 4.5% average for the last 4 years. Spending needs to grow at a minimum of 4.4%/yr. just to stay ahead of construction inflation, otherwise volume is declining. Spending slowed dramatically in 2019. However, new starts in 2018 and 2019 boosted backlog and 2020 spending will post the strongest gains in four years.

Several Nonresidential Buildings Final Cost Indices averaged over 5% per year for the last 2 years and over 4% per year for the last 5 years. Nonresidential buildings inflation totaled 22% in the last five years. Input indices that do not track whole building cost would indicate inflation for those five years at only 12%, much less than real final cost growth. For a $100 million project escalated over those five years, that’s a difference of $10 million, potentially underestimating cost.

Notice in this next plot how index growth is much less for ENR BCI and RSMeans, both input indices, than for all other selling price final cost indices. From 2010 to 2019, total final price inflation is 110/80 = 1.38 = +38%. Input cost indices total only 106/85 = 1.25 = +25%, missing a big portion of the cost growth over time.

Nonresidential Buildings Selling Price Indices vs Input Indices

Non-building infrastructure indices are so unique to the type of work that individual specific infrastructure indices must be used to adjust cost of work. The FHWA highway index increased 17% from 2010 to 2014, stayed flat from 2015-2017, then increased 15% in 2018-2019. The IHS Pipeline and LNG indices increased 4% in 2019 but are still down 18% since 2014. Coal, gas, and wind power generation indices have gone up only 5% total since 2014. Refineries and petrochemical facilities dropped 10% from 2014 to 2016 but regained all of that by 2019. BurRec inflation for pumping plants and pipelines has averaged 2.5%/yr since 2011 and 3%/yr the last 3 years.

Anticipate 3% to 4% inflation for 2020 with the potential to go higher in rapidly expanding Infrastructure markets, such as pipeline or highway. This link refers to Infrastructure Indices.

Construction Analytics Building Cost Index

In the following plot, Construction Analytics Building Cost Index annual percent change for nonresidential buildings is plotted as a line against a bar chart of the range of all other nonresidential building inflation indices. Bars represent the predicted range of inflation from various sources with the solid line showing the composite final cost inflation. Note that although 2015 and 2016 have a low end of predicted inflation of less than 1%, the actual inflation is following a pattern of growth above 4%. The low end of the predicted range is almost always established by input costs (ENR BCI is plotted), while the upper end of the range and the actual cost are established by selling price indices.

Construction Analytics Nonresidential Buildings Cost Index

vs Range of Input Indices

As noted above, some reliable nonresidential selling price indexes have been over 4% since 2014. Currently most selling price indices are over 5% inflation since 2018.

Every index as published has its own base year = 100, generally the year the index was first created, and they all vary. All indices here are converted to the same base year, 2017 = 100, for ease of comparison. No data is changed from the original published indices.

Non-building Infrastructure indices are far more market specific than any other type of index. Reference specific Infrastructure indices rather than any average.

A word about terminology: Inflation vs Escalation. These two words, Inflation and Escalation, both refer to the change in cost over time. However escalation is the term most often used in a construction cost estimate to represent anticipated future change, while more often the record of past cost changes is referred to as inflation. Keep it simple in discussions. No need to argue over the terminology, although this graphic might represent how most owners and estimators reference these two terms.

This link points to comprehensive coverage of the topic inflation and is recommended reading. Click Here for Link to a 20-year Table of 25 Indices

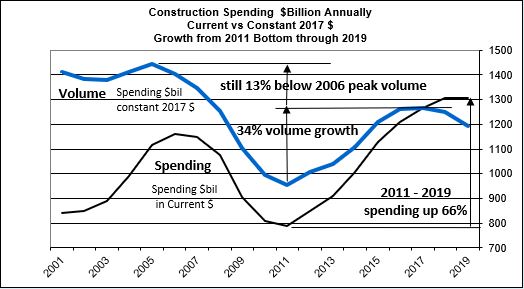

Current$ vs Constant$ – Spending vs Volume

Comparing current $ spending to previous year spending does not give any indication if business volume is increasing. The inflation factor is missing. If spending is increasing at 5%/year at a time when inflation is 4%/year, real volume is increasing by only 1%.

Nonresidential buildings spending increased 3.3% in 2017, 4.4% in 2018 and 0.3% in 2019. But nonresidential buildings inflation for those three years was 3.7%, 5.0% and 5.0%. Nonresidential volume therefore declined for three consecutive years by a total of 5.5%. The current nonresidential buildings forecast spending growth is 3%/yr or less for the next three years. With inflation near 4%, that would suggest inflation adjusted nonresidential buildings construction volume is declining.

Residential spending increased from 2011 through 2017 by average growth of 13%/year. With average residential inflation during that period of 5%/year, inflation adjusted residential volume increased by 8%/year. That changed in 2018.

Residential spending increased only 2.7% in 2018 and dropped 4.6% in 2019. Residential inflation for 2018 and 2019 was 4.3% and 3.6%. Residential volume therefore declined by 1.6% in 2018 and 8% in 2019. Current residential forecast spending growth is +6% in 2020 but then -3.7% in 2021. With inflation just under 4%, that indicates inflation adjusted residential construction volume will grow only 2% in 2020 but may drop 7% in 2021.

In 2018 and 2019, total construction volume declined 6%. Residential volume declined 10%. Construction spending forecast for 2020 is $1,365 billion, an increase of 4.6% from 2019. But 2020 inflation is forecast at 4%. So, after inflation real volume growth in 2020 is forecast up less than 1%. It’s down 1.4% for nonresidential buildings but up 2% for residential.

Nonresidential Buildings will post declines in volume in 2020 & 2021. Non-building Infrastructure volume will increase 1% in 2020 and 4% in 2021. If residential starts hold as forecast at only 1% to 2% growth, residential volume will decline sharply by 7% in 2021 after a moderate 2% gain in 2020. Overall, total construction volume has declined in 4 out of the last 6 quarters and is forecast to drop slightly in 3 of 4 quarters in 2020.

The plot below, comparing inflation adjusted constant dollars with current spending dollars for all construction, clearly shows that although spending is at an all-time high, volume is down the last two years and is lower than all years from 1998 through 2008.

Spending after adjusting for inflation shows volume never got closer than 13% less than the previous 2005 high. Currently, volume is 17% lower than the 2005 peak.

Jobs and Volume

Construction requires about 5,000 workers for a year for every added $1 billion in construction “volume”. But construction jobs growth seems to closely follow growth in spending. Construction jobs have increased by 400,000 in a year only four times in the last 50 years, each time accompanied by one of the four highest spending growth increases in 50 years. However, spending is not the same as volume, and jobs needed is based on volume.

Construction added 1,400,000 jobs in the 5 years 2014-2018, an average of 280,000 jobs/year. The only time in history that exceeded jobs growth like that was the period 1993-99 with the highest 5-year growth ever of 1,483,000 jobs. That same 1993-99 period had the previous highest 5-year spending and volume growth going back to 1984-88.

Although 2020 spending will increase 4.6%, construction inflation has been hovering between 4% and 5% for the last five years. Real volume growth in 2020 after inflation is expected to be only 0.6% or only $7 billion. That would mean the need, if there are no changes in productivity, is to add only about 35,000 additional jobs in 2020.

But the results are much different for Residential than Nonresidential.

Nonresidential spending increased 50% since Jan. 2011 with 35% inflation. Nonresidential volume increased by only 15%. Jobs increased by 27%, 12% in excess of volume growth.

Residential spending increased by 125% since Jan. 2011, but after 40% inflation, real residential volume increased by 85%. Jobs increased by only 40%, 45% short of volume growth.

There are a few reasons why residential construction labor might not be compared easily to residential spending;

- Some residential high-rise jobs, for example structure, are performed by firms whose primary activity is commercial construction. Those jobs are classified as nonresidential.

- Buildings that are multi-use commercial retail and residential, even lo-rise, may be built by contractors whose firms are classified nonresidential labor. The construction spending would be broken out to residential and nonresidential, but the labor would not.

- Some undocumented labor is not counted, and it’s primarily residential.

For these reasons, it is best to simplify comparisons of spending activity to total labor.

Jobs should follow volume growth, yet history shows that in non-recessionary periods, even with volume declining, jobs usually continue to increase, but perhaps at a slower rate.

From 1997 to 2004, it took 4800 jobs to put-in-place $1 billion of construction in one year. By 2008 that increased to 5500 jobs to do $1 billion of work in one year. It remained level at 5500jobs/$1 billion/yr until 2016. In 2018 it jumped to 5800 jobs and in 2019, 6100 jobs, the highest ever recorded.

There has not been any volume growth in the last two years to support jobs growth. In constant$, there was no volume growth in any sector in 2018. In 2019 only Non-building Infrastructure shows 2% growth. Total construction volume is down 1.4% in 2018 and 4.4% in 2019.

In the last two years, spending increased only 2.5%, but construction inflation totaled 9%, therefore, real volume declined by more than 6%, yet jobs increased by 7.5%. From 2006 to 2017, jobs and volume growth were nearly equal. Since 2017, volume and jobs growth is diverging. Construction volume has been declining while jobs have been increasing. That can’t be sustained.

This plot shows predicted 2020 jobs growth of 1.5% or just over 100,000 jobs. Since volume is forecast to gain less than 1%, any jobs growth in 2020 beyond 1% will increase the disparity between jobs and volume growth. The disparity has been increasing since early 2018. It’s a 15% difference right now. Within a year that could be 20%.

By resetting the baseline of this next plot to 2006, the year of the last major divergence in jobs growth vs volume, it shows all other years from 2007 to 2017 were pretty well-balanced growth. With the exception of 2006 and now 2018-2019, for almost every year from 1997 to 2019 jobs grew pretty closely aligned with volume. A big 15% spread occurred in 2006, then growth remained balanced through 2017. The spread now is near the same as it was in 2006.

See post for development of this plot Expect Construction Jobs Growth to Slow in 2020

Volume declines will drive jobs to slower growth. We had 6 years of annual growth of 250,000-300,000/yr. Jobs increased by only 150,000 in 2019. In 2020, growth may be lower to 100,000.

Construction jobs growth slowed substantially the last two quarters. I predicted jobs growth would slow because volume growth had already been declining since early 2018 when volume reached a peak of $1,300 billion. Volume is now $1,200 billion, down 8% in 22 months. After 6 years of jobs increasing at an average 280,000/year, jobs are up only about +150,000 in 2019, but only +70,000 in the last 8 months. The rate of jobs growth is now the slowest in 7 years. I expect this trend to continue.

Volume declines should lead to lower inflation as firms compete for fewer new projects. However, if jobs growth continues while volume declines, then productivity continues to decline and that labor cost growth will add to inflation.

The plot of jobs growth shows current growth rate is below an annual rate of 150,000 jobs/year and it is expected to remain there through 2020, potentially dipping as low as 100,000.

I’d be surprised if jobs start to decline, but that certainly could be envisioned and it would help explain away some of the disparity in growth shown on the Jobs/Volume plot up above.

Predicted Reliability of Construction Forecasting

For any future forecast month, the most information is in hand the month before. Assessing the amount of actual data (jobs in backlog) versus the amount of predicted data gives an indication of how much weight can be placed on the forecast. Obviously, the balance of actual data versus predicted data gets less the further out in time we view the forecast.

For Nonresidential work, most of the spending in any given year comes from projects already in backlog. For nonresidential forecasting, 80% of all the spending in the year comes from projects in backlog. Only 20% of spending in the year is generated from new project starts within the year.

For Residential work, most of the spending in any given year comes from new project starts within the year. Only about 30% of the spending in the year comes from projects already in backlog.

The total amount of work in backlog supports 98% of the forecast in the following month for nonresidential and 94% of the forecast for residential. The amount of known work that will generate spending in the month 12 months out from the forecast date is only 80% for nonresidential work. It’s only 30% for residential work.

For the period only 12 to 24 months out from the forecast date, actual nonresidential data drops from 80% to 30%. Residential actual data drops from 30% to zero.

For all markets combined, accounting for the weighted averages of residential and nonresidential work, once all construction starts are reported to include the data as of Dec. 2019, the 2020 forecast includes 78% actual data and 22% predicted data. The 2021 forecast includes only 40% actual data from starts that have been booked. All the rest of the 2021 forecast is predicted.

Three years out from the current date the reliability of the forecast is dependent entirely on economic outlook and the predictive methodology of the analytic tools, not on actual data. It’s important to know, when you are looking at a forecast that projects three years out past the current year, there may be no “actual” data in that forecast.

Questions regarding this analysis can be addressed to: Edward R. Zarenski – Construction Economics Analyst – Construction Analytics – edzarenski@gmail.com – 401-330-6152

Data used in this report is accessed from the following data sources:

Construction Analytics Economics Reports https://edzarenski.com/

Construction Analytics Inflation https://edzarenski.com/2016/10/24/construction-inflation-index-tables-e08-19/

Associated General Contractors of America AGC https://www.agc.org/learn/construction-data/construction-data-producer-prices-and-employment-costs

Dodge Data and Analytics Construction Starts https://www.construction.com/news

Engineering News Record https://www.enr.com/

Mortenson https://www.mortenson.com/cost-index

Rider Levitt Bucknall https://www.rlb.com/en/index/publications/?geolocation=americas

RSMeans data from Gordian https://www.rsmeans.com/landing-pages/2019-rsmeans-cost-index.aspx

S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CSUSHPINSA

Turner http://www.turnerconstruction.com/cost-index

U.S. Census Construction Spending https://www.census.gov/construction/c30/release.html

U.S. Census Housing Construction Index https://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/pdf/price_uc.pdf

U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics https://www.bls.gov/ppi/ppinrbc.htm

U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics Construction Labor U. S. https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag23.htm

Click here for a downloadable PDF of 2020 Construction Economic Forecast Feb 2020

Click here for a downloadable PDF of SUMMARY – 2020 Construct Econ Forecast 2020

Summary of 2020 Construction Outlook

Construction Analytics 2020 Construction Economic Forecast – Jan 2020 (Excerpt from the complete economic report)

For the full report see 2020 Construction Economic Forecast – Jan 2020

Summary of 2020 Construction Outlook

Total of All construction spending in 2019 is forecast to decrease -0.2% to $1.305 trillion. For 2020, spending increases by 4.6% to $1.365 trillion.

Nonresidential Buildings construction spending is forecast to finish 2019 at $455 billion, level with 2018. For 2020 the forecast is a gain of 3% to $467 billion. Educational and Commercial/Retail held down gains in 2019. Office (which includes data centers) and Lodging gained 7% each. Office, Healthcare and Educational all support growth in 2020.

Residential construction spending forecast is down 5% to $521 billion in 2019 and up 6% to $552 billion in 2020. New starts are recovering from a 10% drop in the 1st half of 2019 and are now expected down only slightly for 2019 after the latest three-month average starts were the highest ever. Residential spending peaked in Q1 2018 and dropped 11% to a low in July 2019. Although spending has since recovered half of that drop, growth in 2019 slowed to less than inflation. Residential construction volume in 2019 dropped 8%, the largest volume decline in 10 years. 2020 volume is forecast to increase 2%.

Non-building Infrastructure construction spending is forecast to increase 7% to $329 billion in 2019 and 5% to $345 billion in 2020. Transportation spending gets strong growth from three years of record new starts. Half of all transportation spending in 2021 comes from projects that started in 2017-2019. Both Public Works and Highway starts have been increasing modestly to reach new highs in 2019. Non-building Infrastructure projects have the highest share of multi-billion dollar projects that spread spending out over longer duration.

In July of the following year the spending data for the previous two years gets revised. Those revisions are always up, although some markets may increase while others decrease. So, even though the current forecast for 2019 spending is down -0.2% to $1.305 trillion, that will most likely increase to a net gain.

In October, Dodge Data forecast their 2019 construction starts to total $809 billion, down 1% from 2018. However, starts are always revised up in the following year. In just the last three years, nonresidential starts have been revised up by 7.5%/yr and residential starts by 2.4%/yr. I expect revisions will show 2019 starts increased by 3% to 4% over 2018. However, even with revisions, 2019 starts will post the slowest annual growth since 2011.

Dodge Data and Analytics new construction starts for November 2019 advanced to the highest seasonally adjusted annual rate ever, resulting in the three months Sep-Oct-Nov 2019 posting the highest 3-mo average ever, 10% higher than the total average for 2018. Several long duration projects started, so a lot of the spending from these new starts will occur in 2021-2022.

Dodge is forecasting 2020 starts down 4%. This forecast includes only 1% to 2% growth in new starts for 2021-2022.

Starting backlog, which increased 5% leading into 2020 is currently at an all-time high, up 20% since 2017. 80% of all Nonresidential spending within the year will be generated from projects in starting backlog. More than 20% of all spending in 2020 is from projects that started more than 3 years ago.

While a few markets will outperform in 2020 (transportation, public works, office), predicted cash flow (spending) from backlog is up only 1% to 2%. Long duration projects added to backlog and will spread spending out over the next few years. Current indications are that 2020 backlog will be up 4% for residential work, 6% for nonresidential buildings and 7% for infrastructure work.

- Starts increased 8%/yr. in 2016 and 2017, but only 4% in 2018.

- Starts are forecast to decline slightly in 2019 and 2020.

- Spending increased 9%/yr. from 2012 to 2016, then slowed to 4%/yr. in 2017 and 2018.

- Spending declined 1% in 2019 and is forecast up 4% for 2020 and 1% in 2021.

- Backlog reaches a post-recession high in 2020, up 20% from 2017, up 100% from 2013.

Since early 2018, jobs have been increasing while construction volume is declining. A declining volume of work does not support jobs growth. When volume of work decreases, jobs should also decrease. If jobs increase, then it results in more workers to produce the same amount of work. In other words, productivity is declining. This could result in one or more of these outcomes:

- Labor demand on hiring drives labor cost up by unexpected amounts.

- New labor coming into the workforce has less experience, lowering productivity.

- Contractors cannot meet schedules, extending project duration.

- Contractors work overtime to meet schedules, adding cost.

All scenarios either extend project duration or drive up the cost of projects or both, which could lead to some unforeseen inflation.

General construction cost indices and input price indices that don’t track whole building final cost do not capture the full cost of inflation on construction projects. Residential and Nonresidential Buildings inflation indices developed by Construction Analytics are final cost selling price indices.

Nonresidential buildings inflation, after hitting 5% in both 2018 and 2019, is forecast for the next three years to fall from 4.4% to 3.8%, lower than the 4.5% average for the last 4 years.

Residential construction inflation in 2019 was only 3.6%. However, the average inflation for six years from 2013 to 2018 was 5.5%. It peaked at 8% in 2013 but dropped to 4.3% in 2018 and only 3.6% in 2019. Forecast residential inflation for the next three years is level at 3.8%.

Non-building infrastructure indices are so unique to the type of work that individual specific infrastructure indices must be used to adjust cost of work.

This link points to comprehensive coverage of the topic inflation. Click Here for Link to a 20-year Table of 25 Indices

This link points to articles related to the Construction Outlook for 2020. Click Here for Link to Construction Economic Outlook 2020

To Support Construction Jobs, We Need Volume

11-2-19

12-6-19 plots updated to include Nov jobs and Oct spending.

Construction Spending IS NOT Construction Volume.

I read an analyst report this week that stated construction jobs growth isn’t keeping pace with construction volume growth. The reference appeared to be to construction spending. That fails to apply inflation to convert construction spending to construction volume, so compares apples to oranges. Spending must be adjusted for inflation to get real volume growth. Jobs MUST be compared to volume.

For over two years now, construction volume growth has not supported construction jobs growth we’ve seen. I expected jobs growth to slow down. I’ve been saying this for over a year. This sure looks like it.

For 2018 jobs growth averaged over 300k. Since January 2019 the rate of jobs growth has dropped from 300k to 150k.

Current projected new starts data IS NOT supporting construction volume growth for the next 2 yrs. Growth of 3%/yr in non-building infrastructure will be offset by declines in residential buildings and flat nonresidential buildings. Therefore, there is no real volume support for jobs growth.

This plot adjusts construction spending by taking out inflation to get real construction volume growth. Last year of real volume growth was 2016. Yet jobs continue to climb. This can’t continue. The plot above shows it has slowed.

Construction jobs growth has slowed considerably over last 2Q, as expected. While construction jobs are up about +150k in last year, jobs (through Nov) increased only +48k in the last 7 months. I’m expecting this trend to continue. In fact, I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised to see in the near future some months when construction jobs decline. The fact is, construction volume simply does not support jobs growth.

Total construction volume, spending after accounting for inflation, has been down for 5 of the last 6 quarters. Volume peaked from Q1 2017 to Q1 2018, but the last year of real volume growth was 2016. Volume is flat or down while jobs continue to rise. This can only mean contractors will be at risk of being top-heavy jobs if a downturn comes.

Caution is advised if putting emphasis on construction JOLTS, which has been climbing to new highs. From mid-2006 to mid-2007, JOLTS reached near the then all-time high. But construction volume, starting in mid-2006, was already on the downward slope. Volume peaked in early 2006 and fell 10% by mid-2007. Construction did not begin shedding jobs until late 2006, but mid-2007, job losses were well underway. Within 12 months, more than 500,000 jobs were gone. Within 18 months, construction jobs were down 1.5 million.