Home » Posts tagged 'labor' (Page 3)

Tag Archives: labor

Construction Jobs – Is July a Turning Point?

8-6-16

The July jobs report issued yesterday gives us labor data to compare to spending. Here’s a few tweets I put out yesterday.

From Sep to Mar spending increased by 4.5% but jobs/hours increased by only 3% = productivity gains. Now seems to be reversing.

Since March, construction spending is down 3.7%, construction jobs are down 0.3%. Beginning to see 2015 productivity gains reset.

Last 12mo Residential Construction Spend up 3%, rsdn jobs up 5%. Next few months room for spend to grow with little jobs growth = Balance

Construction Workforce portion identified as in force but unemployed at 16 year low. Yes, there is a labor shortage.

While the immediate comparison we read is often what happened this month versus last month, for comparison to construction spending it is perhaps better to look at recent longer trends.

- For the 6 month period including Oct’15 thru Mar’16 construction gained 214,000 jobs, the fastest rate of growth in 10 years. Then, after 3 months of losses, July shows a modest gain.

- During that same period Q4’15 spending was flat but by the end of Q1’16 spending had increased more than 4% in 6 months, or at an annual rate of 8% to 9%.

- Even though some upward revision is expected for June spending, total Q2’16 spending will still be down 2% to 3% from Q1.

- Q2’16 jobs declined all 3 months, keeping in mind this immediately follows the fastest rate of growth in 10 years. But it also tracks directly to three monthly declines in spending.

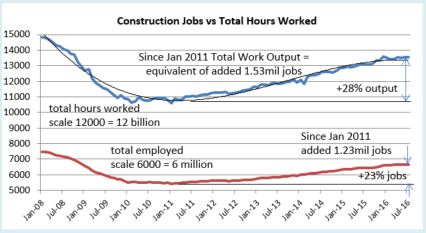

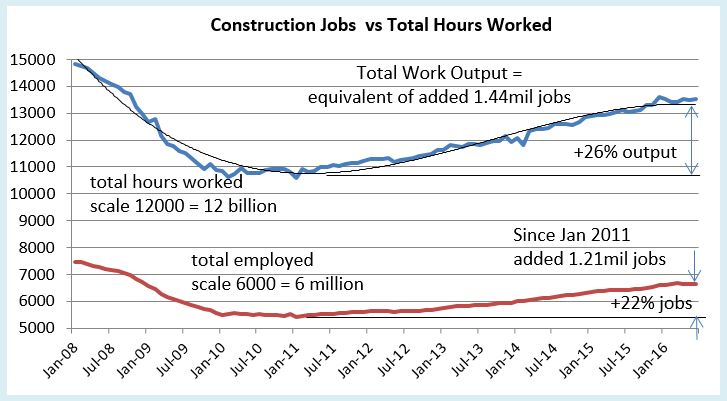

- Since Q1 2011 the constant $ value of construction spending after inflation increased by 30%. Jobs/hours worked output increased by 28%.

It is not so unusual to see jobs growth slowed in these last few months. It follows directly with the Q2 trend in spending and it follows what might be considered a saturation period in jobs growth. The last two years growth was the best two-year period in 10 years. It might also be indicating that after a robust 6 month hiring period there are far fewer skilled workers still available for hire. The unemployed available for hire is the lowest in 16 years.

We got modest growth in July that I hope to see continue for the 2nd half 2016. I expect spending to experience strong growth in the 2nd half and jobs growth should follow closely, perhaps adding 125,000 to 150,000 more jobs. However, although I do expect both spending and jobs growth, jobs could be somewhat restrained by lack of available skilled workers.

June Jobs Report Construction

June Jobs Report (May 15-Jun 18) released July 8

There have been no job gains in construction for the last 3 months. In fact we’ve lost 22,000 jobs since March and have only 46,000 new jobs year-to-date. I have to admit after the Apr and May losses, I expected a sizable jobs gain in June. However, for quite a while I’ve predicted spending would decline in Q1 and since a peak in Mar it’s been going down for 2 months. Lower spending would correlate to lower jobs.

Construction jobs are up 3.9% over the same period 2015, so a temporary slowdown should not have much effect. We have just gone through the best 3 years of construction jobs growth since 2004-2006. Perhaps we may experience a leveling out between spending and jobs. At any rate, I see construction spending increasing. There’s still a lot of spending growth in current backlog from starts, so I expect further increases in jobs.

The available unemployed pool dropped to the lowest in 16 years. That could also have some correlation with slow or no jobs growth, as it may mean the people to hire are not available.

Availability already seems to be having an effect on wages. Construction wages are up 2.6% year/year, but are up 1.2% in the last quarter, so the rate of wage growth has recently accelerated. The most recent JOLTS report shows we’ve been near 200,000 job openings for months. That with this latest jobs report could indicate labor cost will continue to rise rapidly.

As wages accelerate, also important is work scheduling capacity which is affected by the number of workers on hand to get the job done. Inability to secure sufficient workforce could impact project duration and cost and adds to risk, all inflationary. That could potentially impose a limit on spending growth. It will definitely have an upward effect on construction inflation this year.

Construction worker output Q2 2016 (# workers x hours worked) is up 3.7% over the same quarter last year, but up only 0.6% from Q1 2016.

Spending minus inflation (volume) has been growing faster than workforce output for the last few years. Since Jan 2011, volume has increased 20% and workforce output increased 26%, a net productivity loss, but since Jan 2014 volume increased by 16% and workforce output increased by only 12.5%. Total hours worked compared to total spending shows productivity has been increasing for the last two years. It would be unusual to see productivity growth continue for another year. This leads me to think if spending plays out as expected then construction jobs will grow by about 200,000 in 2016. Availability could have a significant impact on this needed growth.

Trump’s Wall

5-22-16 updated 1-7-19

Trump’s Wall

Recently I received a call from a major national news source. They asked for help understanding what it would take to build “Trump’s Wall.” I’m an estimator, so I provided some realistic analysis of what it would take.

The border with Mexico is almost 2000 miles long. There is already about 700 miles of fence. This analysis makes an assumption it would be necessary to build only 1000 miles of wall. Also, this estimate is based on the type of wall you see along highways, precast concrete sound and site barrier wall. In reality it would need to be significantly more robust than the typical highway sound-barrier wall, and I’ve taken that into consideration in my estimate. So here goes.

(9-1-16 >>In some other recent articles I’ve read they have suggested a 40 foot high concrete wall. Well, I don’t think you can build a 40 foot high unsupported concrete wall (no bracing at sides) without getting into extremely massive volumes of materials. Such a high concrete wall would need to be much thicker at the base than at the top and the foundation to prevent overturning would need to be massive. Typical rule of thumb for foundation to prevent overturning is the foundation needs to be ~40% as wide as the height of the wall. The volume of concrete would be 4x to 5x what I’ve estimated for the wall I’ve defined here and the excavation, back fill and formwork would add considerable time to complete. Order of Magnitude I guess 40 to 50 million cubic yards of concrete for wall and foundation. I would roughly guess such a massive poured concrete foundation and wall, if it could even be built, would cost THREE TO FOUR TIMES what I’ve estimated here and would require substantially more labor and might take twice as long or more to build.)

This estimate is based on 8″ thick precast heavily reinforced concrete wall panels set between steel columns 12’0 on center. Even if the concrete could be chipped away, the reinforcing bars would prevent passage. Columns are set in 6’0 dia. x 10’0 deep column foundations. Between column foundations under the wall is a continuous footing to help resist overturning of the wall. The wall extends 25 feet above grade and 5 feet below grade. Bottom of concrete footing under the wall is 7’0 feet below grade. Bottom of column foundations is 15’0 below grade. The wall would be much higher than the approximate 12′ shown in the representative photo.

The foundations included here are based on up-sizing components from a known design for a 15′ high prison un-climbable open-mesh fence. Even with an open mesh fence design, to overcome wind load, column footings were 2″0″ dia x 8’0″ deep concrete post foundations set every 8′ apart. This solid wall 25′ high would have enormously greater wind loads and it is the foundation that must be designed to prevent overturning.

Just to get quickly to the end, I calculated the final cost of a 25′ high precast wall, foundations, excavation and access roads in the vicinity of $25 billion (in 2016 $), $10 million per mile or slightly less than $2,000 per lineal foot of wall. I’m fairly certain this estimate is somewhat low and the actual cost due to the many unknowns would be higher. At the end I’ve pointed out some of the issues that could generate unknown costs.

One huge factor is inflation. Historical average construction inflation is greater than 4%/year. If a $25 billion wall takes 10+ years to build, the total cost over time assuming the historical average construction inflation would be $30 billion.

This is a summary of some of the results from the concrete wall estimate.

Materials

200 million square feet of precast concrete panels = 5.2 million cubic yards of concrete

5 million cubic yards of cast-in-place concrete foundations

Total cement to make the 10.2 million cubic yards of concrete = 2% of annual US cement production.

1.5 million tons of steel = 1.5% of annual US steel production.

25 million cubic yards of excavation required.

6 million cubic yards of that excavated earth must be hauled away and disposed since that volume will be replaced underground with concrete. That’s more than enough to completely fill the Superdome. Or, it’s enough to build a 20 foot wide earthen embankment 20 feet high and 100 miles long.

Delivering the Materials

250,000 truckloads of precast wall panels,

500,000 truckloads of ready mix concrete

50,000 truckloads of steel

200,000 truckloads to haul away excess excavated earth.

This is far from a complete list of materials, because in addition to building the wall, in some places you first need to build a road. Assume about 500 miles of road. You can’t get 1,000,000 truckloads of 30-40 tons each, cranes, excavators and auger drills to a construction site without at least building a compacted gravel road to get there.

Adds 2 million cubic yards of stone for construction equipment road.

Adds 100,000 truckloads of stone

Labor

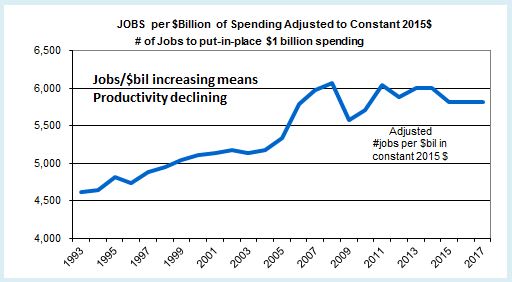

It takes 5000 to 6000 workers to build $1 billion worth of construction in 1 year.

$25 billion x avg 5500 = 135,000 man-years, or 135,000 workers if it is to be built in 1 year. Or it would take 10,000 full-time workers 13.5 years to build this concrete wall.

If 1,000 men worked on the wall 5 days a week 8 hours a day, it would take 135 years to build it. Therefore, I made the assumption the project would be broken into 50 segments each 20 miles long and looked at two scenarios. What labor would be required to build it in 10 years or 4 years?

4 years: That will require 700 men AT EACH of 50 SEGMENTS concurrently to complete the wall in 4 years. That’s 35,000 men working for 4 years. That is 35,000 trades-worker jobs which does not include Architect, Engineering, Testing and General Contractors management personnel.

1,100,000 truckloads at 50 locations over 4 years is = 20 deliveries per day of 30 to 40 tons each at each of the 50 locations. That works out to 40 truck bypasses per day coming and going, so 30 ton trucks go by (some community) every 12 minutes at every one of 50 locations every workday for 4 years. It is very likely that heavy truck traffic will destroy many if not all the town roads used to access the 50 construction sites. The cost to repair/replace those existing roads is NOT included here, but I suspect it would be in the hundreds of millions.

The 4 year scenario is quite unlikely from just about every standpoint. Labor availability, engineering studies and site preparation of 50 (or more) job sites, mobilization of 35,000 men to 50 job sites, product supply, frequency of deliveries, overcrowding of job site. In reality, 700 men at a job site is probably far more than can be managed. In this scenario the number of job sites would need to be increased, probably to more like 150 to 200 individual job sites. While all aspects seem to limit this choice as viable, it is probably labor and material availability that would have the greatest impact.

10 years: To build the wall in 10 years would require 13,500 workers, or about 250 workers AT EACH of 50 SEGMENTS concurrently to complete the wall in 10 years. That’s 13,500 workers working for 10 years. That is 13,500 trades-worker jobs including General Contractors management personnel but not including Architect, Engineering, Testing, Manufacturing and Delivery.

1,100,000 truckloads at 50 locations over 10 years is = 8 deliveries per day of 30 to 40 tons each at each of the 50 locations. That works out to 16 truck bypasses per day coming and going, so 30 ton trucks go by (some community) every 30 minutes at every one of 50 locations every workday for 10 years. The same heavy truck traffic will destroy many if not all the town roads used to access the 50 construction sites, it just takes longer. The cost to repair/replace those existing roads is NOT included here.

The 10 year scenario is certainly not impossible. Labor availability and mobilization issues are reduced as are product supply and frequency of deliveries.

NOTE 1-7-19 New review of proposed steel barrier changes some materials and has a moderate overall affect on total cost, manpower and time to complete. In question is size of steel section that could withstand installation 25′ to 30′ tall unsupported. For a steel barrier estimate I used tube steel hollow structural sections (HSS) 8x8x3/8 set with 6″ spaces between. The summary from the estimate revises precast panels to 3 million tons of steel. The remainder of the summary is still valid. It changes a little. Total cost came in near $24 billion versus the original estimate for precast concrete wall at $25 billion. However if design would require a heavier section 8x8x1/2 then cost jumps to $29 billion. If design requires concrete filled tubes cost would go up by about $750 million. If 8×8 tubes are rotated 45 degrees, spacing can be reduced and open spaces between tubes can be reduced, steel cost would go down by about $1 billion. Foundation cost may or may not be reduced (by as much as $2 billion), but foundation design to prevent wall overturning is more dependent on wind load than on the weight of the steel above. In any case foundations are massive and still calculate out to about 5-6 million cubic yards of concrete and proximity of concrete batch plants to construction zones could be a major issue. Keep in mind none of this cost includes land acquisition, inflation, housing workers, change orders or building new plants to support job sites with materials.

Best case scenario, at the low end of cost at $22 billion, it would take 10,000 men 11 years to build 1000 miles of steel fence barrier. It is likely that the low end estimate is much to optimistic, citing some issues outlined below.

A word about HSS steel tubes. US annual production for Hollow Structural Sections in 2016 was 1.6 million tons per year. That annual demand does not go away if 3 million tons of tube steel is needed for a wall. Over a period of 10 years, at 0.3 million tons/year, steel needed for a wall would be 20%/year of tube steel production. To prevent shortages, production capacity must increase or that extra tube steel must be imported. The US imports about half of all the steel pipe and tube is uses in a year from South Korea, but most of that is oil industry pipe. Manufacturing mills typically cannot increase capacity by 20% in a year. So, this extra demand for tube steel would either cause shortages or increase imports.

Energy cost just to produce 3 mil tons of steel is enough to power 500,000 homes for 1 year. Energy to produce both steel and concrete probably more than doubles that number.

The money spent is enough to build 70,000 new homes or 500 new high schools.

Gasoline just for all truck deliveries is near 5 million gallons.

The concrete and steel materials gross to 2% of annual US cement production and 1.5% of annual US steel production (for a precast wall), but that represents close to 3% of steel used in construction. (The revised steel barrier reduces precast but increases the steel to 4% of US steel production. It represents 200% of annual tube steel production). About half of all US steel goes into your refrigerators, cars, etc., the other half goes into construction. The materials demand has far more affect than you might think on disrupting normal construction flow. Since it is all localized in one area of the country, the far southwest border, it could potentially represent 20% and 30% of the construction materials capacity in that area of the country, straining the capacity in that area and disrupting the normal volume of construction there for years. This would be detrimental to the rest of the construction industry growth in that area for that period.

This does not address the fact that manufacturing facilities to produce and fabricate the steel and deliver concrete needed at each of the 50 work sites ideally should be spread along this 1000-mile corridor, which is very unlikely. In fact, I suspect it more likely that some locations will not be in close proximity to a materials source, the result either driving cost up or extending duration beyond 4 years, or both. It could require building process plants along the path, for instance, ready-mix concrete batch plants and steel fabrication yards.

The time necessary for land acquisition, design, permitting, environmental study, mass material procurement, construction process planning and mobilization would be many months before construction begins. Although labor availability and the number of sites determines construction duration, 4 years would be a reasonable estimate for construction ONLY IF the 35,000 trades-workers needed can be mobilized simultaneously to 50 job sites, but that is not likely. The 4 years of construction starts when planning, design and permitting are complete. That might take 6 to 12 months.

Construction is experiencing what may be the tightest labor market in over 20 years. Since there are few if any available workers to shift to these new job site locations, we would need to assume much of this work is supported by creating nearly 35,000 new jobs. I looked at the Bureau of Labor Statistics Jobs for metropolitan areas within 100 miles of the border. Several serious problems arise.

In this localized area of the country, along a 1000 mile long 100 mile wide strip, 35,000 construction jobs could potentially be 12% to 15% and possibly as much as 20% expansion of the construction workforce. The maximum 30 yr historical rate of annual construction workforce expansion is 6% nationwide. Normal annual jobs growth is 3% to 4%/year. If one project were absorbing all of the jobs growth in an entire region, there would be no workers available in that region for any other construction activity growth for several years. That’s a major disruption to the local economies of several states.

Such an expansion would be extremely difficult to implement that quickly. The mobilization of 35,000 workers could take a very long time from initial ramping up to full employment, therefore extending the duration to complete the job. Many of these workers could be inexperienced adding further to the project duration. So reaching completion of this work with 35,000 workers would probably take much longer than 4 years. Adding time for planning and more time for ramping up labor, it could be 6 years.

Ramping up then down will soften the blow as the jobs begin to disappear at project completion. It could be pretty hard to generate enough new volume of work to keep all those men working. It will take new volume of $5 billion to $6 billion a year to keep all these workers working.

There’s a great deal to consider about the demand on the workforce to build a border wall, or fence. Let’s look just at Texas. In Texas, there are a total of 775,000 construction workers, the 2nd largest construction workforce in the country next to California. But checking all the major metropolitan statistical areas within 200 miles of the border there are only about 100,000 construction workers. Only about 20% of those workers conduct business in earthwork, concrete and steel, the trades required to build this fence. That’s only 20,000 workers available within 200 miles of the border.

Furthermore, the Texas/Mexico border is 1,250 miles long. If 20,000 workers were spread out evenly along the border (which is most certainly not the case), within any 200 mile stretch and within 200 miles inland, there would be only 3,200 available workers. In some well-populated areas there might be double that, approximately 6,000 workers, but in the less populated areas, there are far less than 3,000 workers within 200 miles of a proposed work zone.

Now let’s assume we need enough workers to build 100 miles of steel fence, somewhere within a 200-mile length and near a well populated area. That’s $2.5 billion of fence. We know that it takes about 5,000 workers a year (5,000 worker-years) to put-in-place $1 billion of construction. So, we need to fill 12,500 worker-years or job-years. That could be 12,500 jobs for 1 year or 1,000 jobs for 12.5 years. How many jobs get filled determines how long it will take to build 100 miles of fence. Well, there are nowhere near enough workers to fill 12,500 jobs to build 100 miles of fence in one year along many sections of the border. In the best case, most of 6,000 workers need to be accommodated with living quarters somewhere along a 200-mile stretch and 12,500 work/years divided by 6,000 available workers means it would take a little over 2 years to build 100 miles of fence.

So, 100 miles of fence would take over 2 years to build, ONLY IF this project could absorb every single available worker in these trades within 200 miles for a period of two years. At the same time, for that 2-year period, there would be no available workers in sitework, concrete and steel trades anywhere else within 200 miles to fill all other normal workload. In less populated areas with only half as many workers available, it would take twice as long, or more.

This brief analysis of cost and constructability does not begin to address issues such as, how would a wall be built anywhere along the 1,000 miles of the Rio Grande river, the border between Texas and Mexico, the 4th largest river in the United States. Assuming such a wall must be built on US soil, a wall would then completely cut off river access from the United States? Or, how would a wall be built through the hundreds of miles of national parks and national wildlife refuges along the border without disrupting natural wildlife migration flow? And, how would it be designed along its 1,000 mile corridor to accommodate drainage across a solid impervious barrier? It seems impractical or at the very least massively environmentally disruptive.

You can see, the logistics would be enormous, impediments loom, adjacent communities would be adversely impacted, the cost is probably far more than the $25 billion estimated and it seems highly unlikely this could ever be completed during the course of a single president’s term.

Construction Volume Growing Faster Than Jobs, and That’s a Good Thing.

2-24-16

The most talked about reason for slower jobs growth is the lack of experienced workers available to hire. In fact, recent surveys indicate about 80% of construction firms report difficulty finding experienced workers to fill vacant positions. That certainly cannot be overlooked as one reason for slower jobs growth, but is that the only reason?

Even with all this talk of difficulty finding experienced construction workers, there is a lot of hiring going on. For the 5 year period 2011-2015 we added 1,100,000 construction jobs with the peak growth rate in 2014 at 6.1%. Jobs increased by 20% in 5 years.

For the two years 2014 + 2015 we added 650,000 jobs, the largest number of jobs in two years since 2004 + 2005. In that two years, jobs expanded by 11%, the fastest percent growth since 1998-1999, the fastest pace in 17 years. But peak growth was in 2014 with slower growth in 2015. I expect even slower growth in 2016.

Construction spending hit bottom at the same time as jobs, the 1st quarter 2011. For the same 5 year period 2011-2015 construction spending increased far more than jobs growth. Why is it that jobs don’t increase at the same rate a construction spending? Because much of that spending growth is just inflation. When describing a shortfall of construction workers, jobs growth should not be compared to spending growth. After adjusting for inflation from Q1 2011 to Q4 2015, we find that construction volume increased by 22% in 5 years.

Now it looks like over 5 years jobs seem to be growing nearly the same as construction volume. It even looks like productivity increased, but that’s still not the whole picture.

Real work output growth is total jobs adjusted by the hours worked each year. From 2011 to 2015 construction hours worked increased by 3.6% from near the lowest on record to the highest ever recorded. The reason this has such a huge effect is hours worked gets applied on all 6.5 million jobs, not just the new jobs added. So, a workforce that grew by 20% worked 3.6% longer hours showing that net total work output actually increased 24.3%.

This data shows that over the last 5 years new volume increased by 22% while work output to produce that volume increased by 24%. Data clearly indicates we have added more work output than the volume of work we have produced. This indicates a drop in productivity over the last 5 years.

It is not uncommon at all that productivity declines during rapid growth. This pattern of growth appears prominently in the last two expansions between 1996 and 2006. Firms may be increasing staff based on revenue without strict attention to real volume growth, only to then slow jobs growth and allow volume production to catch up.

By measuring to previous productivity levels, we could say the construction workforce is currently overstaffed. Of course, spending (and net volume after inflation) is expanding rapidly and with it so must the workforce. But, if there is any hope that eventually productivity will return to previous levels, then we must hope for a minimum increase of 2%+ in volume with no matching additional increase in new jobs or hours worked.

Over the next two years I predict construction spending will increase close to 20%, BUT construction volume will increase only 10%, most of that in 2017. In a previous post, “How Many Construction Jobs Will Be Needed” I predicted jobs will grow by 500,000 to 600,000, only about 8%.

Filling positions with workers less qualified than those who were lost accounts for some of the decline in productivity. Working longer hours also leads to productivity loss. To regain lost productivity, new workers need to gain experience AND overall hours need to be reduced and that workload replaced with new jobs. That’s certainly not likely to happen all in one year, but it may account for some of the reason why volume is currently growing faster than jobs, and that’s a good thing. I expect that will continue at least for the next two years.

Overtime Isn’t Always What It Seems – Lost Productivity Construction

1-30-16

It is sometimes necessary when the situation dictates to increase working hours to achieve a shortened schedule. However, numerous studies can be found to support that Overtime results in lost productivity. There are other factors that affect productivity, but just to address the topic of Overtime, for the moment they will be ignored. This productivity loss set of data is from Applied Cost Engineering, Clark and Lorenzoni, Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1985.

As both hours and number of days worked increases over 5 days and 8 hours, productivity declines. 5 days and 8 hours is considered the norm = 0% productivity loss. Any increase in hours or days above this norm reduces productivity. All values approximate and % loss is loss of production on ALL hours worked.

5 days and 8 hours = 40 hrs @ 0% productivity loss = 40 hrs productive

5 days and 10 hours = 50 hrs @ 7% productivity loss = 46.5 hrs productive

5 days and 12 hours = =60 hrs @ 12% productivity loss = 53 hrs productive

6 days and 8 hours = 48 hrs @ 3% productivity loss = 46.5 hrs productive

6 days and 10 hours = 60 hrs @ 17% productivity loss = 50 hrs productive

6 days and 12 hours = 72 hrs @ 25% productivity loss = 54 hrs productive

7 days and 8 hours = 56 hrs @ 7% productivity loss = 52 hrs productive

7 days and 10 hours = 70 hrs @ 20% productivity loss = 56 hrs productive

7 days and 12 hours = 84 hrs @ 28% productivity loss = 60.5 hrs productive

Not only does overtime produce lost hours, but the cost of the overtime hours increases. Hours over 8 might cost 1.5x normal rate. Days over 5 might cost 2x normal rate. Increasing days and hours rapidly balloons the cost of completing the work. However, if absolutely necessary to meet unusual schedule demands, the cost vs time to complete work can be modeled for each scenario and the least destructive option (whether that be cost constrained or time constrained) can be agreed upon by all parties. The best choice is always that which requires the minimum added cost to achieve the restricted schedule.

See this blog post for an example Construction Overtime – A Common Miscalculation

Construction Forecast 1st Look – What To Expect in 2016?

Construction spending may reach historic growth in 2016.

There are currently six estimates available forecasting 2016 total construction spending ranging from 6% to 10% growth, with an average of 8.7%. My forecast is 9.7%.

Total construction spending, forecast to grow 9.7% in 2016, could reach a total 30% for the three years 2014-15-16. The only comparable periods in the last 20 years are 29% in 2003-04-05 and 27% in 2013-14-15.

The current nonresidential buildings construction boom could become an historic expansion. Nonresidential buildings spending is forecast to grow 13.7% in 2016. Added to 8.8% in 2014 and 17.1% in 2015, the three-year total growth could reach 40% for 2014-15-16. The only comparable growth periods in the last 20 years are 40% in 2006-07-08 and 32% in 1995-96-97.

For perspective, residential spending increased 46% in 2013-14-15, similar to only one comparable period in the last 20 years, 48% in 2003-04-05.

Non-building infrastructure projects, in two of the last three years have barely shown any gains entirely due to declines in power plant projects. This will repeat in 2016.

This is still the 1st or 2nd most active 3 year period of growth in construction in more than 20 years, and it’s already been ongoing since 2013-2014. With the forecast for 2016, spending growth could reach a new three-year high.

From the middle of Q1 2016 to the end of Q3 2016, total spending will post six to eight months at an annual growth rate of 20%, but due to the dips at the beginning and the end of the year, total 2016 construction spending will finish at 9.7% growth. Construction spending momentum is not yet losing steam. We may be seeing the effects of a few years of erratic growth patterns and a shift from more rapidly changing commercial and residential work to slower growth institutional work.

Residential spending will slow several percent early in 2016 before resuming upward momentum to finish the year with 12% growth, slightly less than growth in 2014 and 2015. Periods of low new start volumes need to work their way thru the system and this produces growth patterns with periodic dips. The upward momentum will carry into 2017.

Nonresidential buildings spending will slow moderately in the next few months before we see a 15% growth rate through the middle of the year, only to see another slowdown late in 2016. Major contributions are increasing from institutional work in educational and healthcare markets. Office, commercial retail, lodging and manufacturing will decline considerably from 2015 but still provide support to growth.

Infrastructure projects spending will decline over the next six months due to the ending of massive projects that started 24 to 42 months ago. There will be large advances in spending midyear before we experience another slowdown later in 2016. Following a 0.5% increase in 2015, spending will increase only 1.2% in 2016, held down by a 10% drop in power projects, the second largest component of infrastructure work.

Construction added 1.0 million jobs in the five years 2011-2015. 800,000 jobs were added in the last three years. To support forecast spending, jobs need to grow by 500,000 to 600,000 in 2016-2017. Growth in nonresidential buildings and residential construction in 2014 and 2015 led to significant labor demand which has resulted in labor shortages in some building professions. Demand in 2016-2017 will drive up labor cost and may slow project delivery.

Spending growth, up 35% in the four-year period 2012-2015, exceeded the growth during 2003-2006 (33%) and 1996-1999 (32%) which were the two fastest growth periods on record with the highest rates of inflation and productivity loss. Construction spending growth for the period 2013-2016 is going to outpace all previous periods.

Construction inflation is quite likely to advance more rapidly than some owners have planned. Long term construction cost inflation is normally about double consumer price inflation. Construction inflation in rapid growth years is much higher than average long-term inflation. Since 1993, long-term annual construction inflation for buildings has been 3.5%, even when including the recessionary period 2007-2011. During rapid growth periods, inflation averages more than 8%.

For the last three years the nonresidential buildings cost index has averaged just over +4% and the residential buildings cost index just over +6%, however, the infrastructure projects index declined. The FWHA highway index, the IHS power plant index and the PPI industrial structures and other nonresidential structures indices have all been flat or declining for the last three years. This provides a good example for why a composite all-construction cost index should not be used to adjust costs of buildings. Infrastructure project indices often do not follow the same pattern as cost of buildings.

Anticipate construction inflation of buildings during the next two years closer to the high end rapid growth rate rather than the long term average.

How Many Construction Jobs Will Be Needed to Support 2016-2017 Spending Forecast?

1-12-16

This is a pretty straight forward analysis. If productivity is to remain the same, then jobs need to grow by the same percentage as volume. If volume grows faster, then productivity increases. If jobs grow faster, then productivity declines. Let’s have a look at the numbers to find out what’s been going on and where we might be headed. Spending forecasts will give the basis for predicting jobs growth.

A few weeks back I commented on a study published by Bureau of Labor Statistics on how many construction jobs would be created by 2024. BLS Says +790,000 Construction Jobs by 2024. Let’s Look Behind The Headlines. Now that I’ve completed updating spending and jobs data and developed a forecast for 2016-2017, I will show what has taken place over the last 4 years and what to expect for the next two years.

Here’s what we know.

Volume is not the same as construction spending. Spending is the number nearly everyone follows. Volume is spending minus inflation. I use composite inflation factors based on tracking numerous construction selling price indices.

In 2015 nonresidential buildings spending grew by 17%, but after inflation, volume grew by only 12%. Overall construction spending in 2015 grew by 11%. Total all construction volume grew by 8%. Annual construction inflation varies for residential, nonresidential buildings and nonresidential infrastructure.

For the four years 2012 through 2015 construction spending grew by 35% but after inflation volume grew by 21%.

Work output grows by number of new jobs added and by any increase in total hours worked. For the four years 2012 through 2015 construction jobs increased from 5.5 million to 6.4 million, or 16%. In addition hours worked by the entire 6 million workforce increased by 2%. So effectively, total workforce output increased by 18%.

The last four years volume grew 21% and the effective number of jobs grew 18%. There was an increase in productivity over this four year period of 3%. An increase in productivity occurred because we put-in-place more volume than the (effective) number of jobs added.

Now we can ask the question, “How many construction jobs will be added in the next two years if we achieve the spending forecast?”

Let’s use what we know and apply it to the forecast.

I’m forecasting 10% spending growth in 2016 and 12% in 2017. I anticipate higher inflation than we have experienced in the last few years. After inflation, volume should grow 4% and 6%. So, total volume growth for the next two years is forecast 10%.

With rapid growth, I would expect productivity to decline slightly, but the last 4 years of growth showed a slight productivity gain, so let’s go with that. That means we will lower our estimate of jobs needed because some of the increased volume over the next 2 years will be supported with increased productivity.

Total volume growth for the next two years is forecast at 10%. If we follow the same pattern as the last 4 years, we may see an increase in productivity of 2%. So we need only an 8% increase in workforce output to put-in-place the forecast volume. The average number of jobs for 2015 is 6.4 million. An 8% increase in 2 years on the 6.4 million means we need to add 512,000 jobs in 2016-2017.

If we do not see gains or losses in productivity we need to add 10% to jobs, the same percentage jobs as we have volume growth. That would be 640,000 new jobs in 2016-2017.

As a result, based on this analysis expect a need of about 500,000 to 600,000 new construction jobs in the next two years.

For comparison, in 2014-2015, 601,000 new jobs were added. Then, spending grew 20% but volume after inflation was 12%. Jobs grew by 10%.

Jobs have increased more than 600,000 in two adjacent years only a few times. Any two years within 1996-1998 were over 600,000, also 83-84 and 93-94. The highest ever was 1998-99 when we added 770,000 new jobs, and that two year period had the same total jobs as 2014-2015. The only other recent high periods are 2004-05 added 700,000 and 2014-15 added 601,000.

Also, it’s easy to see now, had this been based on total spending increases for the two years rather than volume, the need would be 20+% or 1.0 to 1.2 million jobs, not just the 8% or 10% jobs growth used here. The last time jobs grew by more than 10-12% in two years was 1977-1978 at 18% and the highest growth ever was 770,000 jobs added in 1998-99, the only time over 700,000. So, as expected, 20+% growth and a million jobs in two years has never been reached.

BLS predicted construction will add 790,000 jobs over 10 years, the period from 2015 through 2024. In 2015 we’ve already gained 260,000 jobs so that would leave 530,000 new jobs expected over the remaining 9 years.

The spending forecast and past job growth patterns indicate that we will add far more jobs and much faster than is predicted by BLS.

Of course, another recession would alter this, but this is not based on another recession.

BLS Says +790,000 Construction Jobs by 2024. Let’s Look Behind The Headlines.

In a report released December 8, 2015 the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) predicts jobs growth for industries. Construction is pegged as a leader with expected 790,000 new jobs from 2014 to 2024. Robert Deitz at NAHB provides a good summary of the BLS report.

Let me provide a few historical averages and break this down so we can see how it stacks up.

The prediction period is from 2014 through 2024, so all of 2014 is already in the BLS baseline. The average number of construction jobs in 2014 was 6,138,000 and BLS uses that baseline. BLS says 2024 will average 6,928,000 construction jobs, growth of 790,000 jobs over 10 years, from which we can infer 12.9% growth in 10 years or a 1.22% compounded growth rate.

In 2015 we’ve already gained 215,000 ytd through November. The average jobs for 2015 is currently 6,390,000, so that leaves 540,000 expected over the remaining 9 years. That would imply a growth rate of 8.5% in 9 years or an average compounded growth rate of only 0.9% per year.

Now here is where it gets interesting.

Spending growth is predicted by several firms between 5% and 10% per year for the next 4 years. My own forecast has 2016 growth at 11%. Average of forecasts for the period 2016-2019 are currently 8%, 7.5%, 6% and 7%.We need to take out inflation to get real volume growth, so we will assume 4% inflation per year for the next 4 years. Long term construction inflation is 3.5% per year, but in rapid growth years it has reached 6%-8% per year. For the period 2013-2015 construction inflation averaged 4%. Adjusting for inflation at 4% results in volume growth for 2016-2019 at 4%, 3.5%, 2% and 3%. This is much faster growth than the BLS average, so we will remain more conservative in this analysis.

Historical volume growth over the last 22 years is grossly distorted by the recession. Volume declined in 8 of those 22 years. In the three worst three years of the recession, 2008, 2009 and 2010, volume declined by 28%. When we take out those three years the typical growth period averages are more apparent. The historical average volume growth in construction with recession data removed and after adjusting for inflation is 2% per year for 19 years.

Jobs growth over the last 20 years averaged 1.6% per year, even when we include the catastrophic losses during the recession years of 2007 through 2010. The BLS is predicting 1.22% growth for 10 years, lower than the average with a recession. Without the four worst recession years of job losses the average growth jumps to 3.7% per year, almost triple the BLS predicted growth. Minus the recession years, there has never been a prolonged period where jobs growth has averaged growth less than 2% per year, so we shouldn’t expect such low growth.

BLS assumes productivity will increase 1% per year. This would lower the number of jobs needed. Construction productivity has never done this before. My records show over the last 20 years there has not even been two consecutive years of construction productivity increases. Long term productivity in the construction industry has declined by 1% per year. Data would indicate jobs growth must be greater than volume growth to make up for productivity losses.

We have differences based on my analysis of historical growth and productivity. Forecasts show expectations of rapid growth in the next few years. These differences would produce dramatically different estimates of jobs growth in coming years. How much different? Let’s see.

Let’s be conservative with assumptions. Based on:

- No productivity increases or losses. Therefore jobs will grow at the same rate as volume.

- Volume growth of 1.5% per year will be less than forecast and less than the historical non-recession average. This allows for some years to decline.

- There will be no recession, but there will be down years.

- Starting from 2015 baseline of 6,390,000 jobs

Jobs need to grow at 1.5% per year compounded for 9 years. That’s 14.3% in 9 years from the 2015 baseline of 6,390,000. Growing 14% in nine years adds 895,000 jobs by 2024. We’ve already gained 215,000 jobs in 2015. For the period of the BLS analysis, my conservative prediction is a total gain of 1,110,000 jobs over 10 years, 320,000 more than the BLS prediction.

Jobs reached a peak in 2006-2007 at 7,700,000. At conservative growth rates we will not reach the previous peak by 2024. However, if construction volume and jobs growth follow a little more closely to historical 20 year patterns, we will add 1,300,000 jobs from 2014 to 2024, but still be short of the previous peak. This scenario adds 500,000 to the BLS prediction.

If volume growth does reach forecast levels and if jobs growth does include some losses in productivity then my estimate for jobs is double BLS and we could reach the previous peak in jobs several years earlier.